I have been searching for Thomas Cromwell’s quylte of yelow Turquye Saten for some years now. What I mean is, of course, that I’ve been looking for any traces of it in anything other than Cromwell’s will (and of course in Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy). I don’t expect to find the actual object – it is highly likely to be long gone, such is the nature of old textiles.

But I have become a bit obsessed by knowing what happened to this high value item. In his 1529 will, Cromwell left his yellow quilt to his son Gregory. However, many of Cromwell’s possessions were seized after his arrest and execution in 1540: so whether Gregory ended up with the quilt is questionable. I’ve started to look into documents relating to the King’s Wardrobe, and note that some of Cromwell’s textiles were listed there – does this include the yellow quilt? I will be taking a closer look in the coming weeks.

A few days ago, I was reading a 1527 inventory of Cromwell’s possessions, and noted a reference to a second quilt- a “yerdure coverlid” or “detailed green quilt” (as listed in Caroline Angus: My Hearty Commendations: The Transcribed Letters and Remembrances of Thomas Cromwell). And a closer look at Cromwell’s 1529 will indicates a bequest of another coverlet or quilt to be left to “Elizabeth Gregory, sometime my servant”.

My quilt search has given me the perfect excuse to spend some very pleasurable days at the National Archives looking at Sixteenth Century documents. I have seen beautiful things, been frustrated by tightly rolled layers, learned to read a little bit of Secretary Hand – and cursed my lack of Latin. So far I haven’t come across any references to Cromwell’s quilts but I am loving the process of looking.

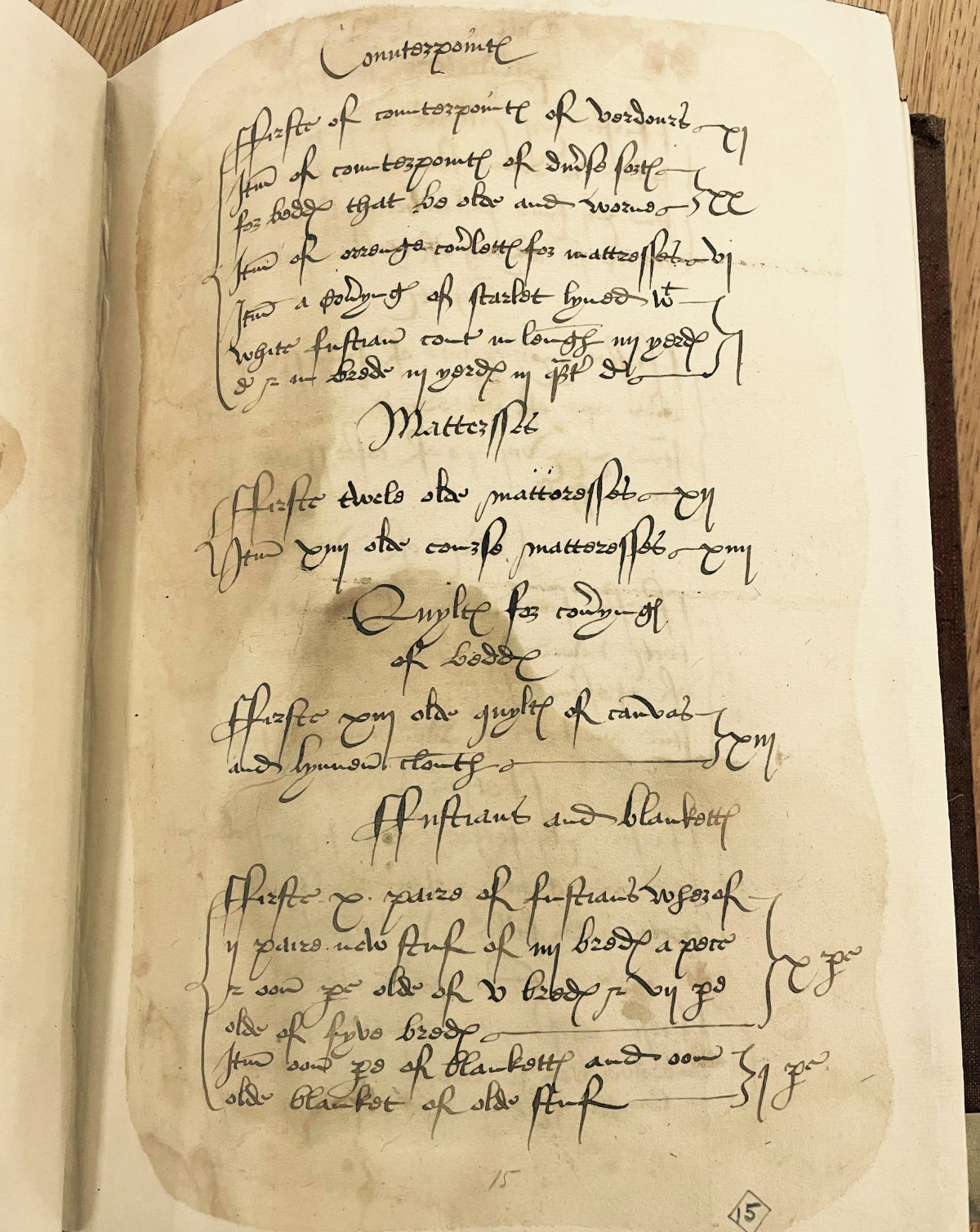

And I was delighted to recognise the word Quylte when I finally saw it – even thought it was a quilt belonging to someone else. In an inventory of Cardinal Wolsey’s goods taken at Cawood in about 1530, there is a “Quylte for covyring of bedde” and “another very old Quylte”.

Of course that inventory sent me straight back to the Cromwell Trilogy. In Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel imagined George Cavendish, Wolsey’s Gentleman Usher, telling Cromwell about Wolsey’s arrest at Cawood in November 1530 – the context in which this real inventory, including its quilts, would have been taken.

In Mantel’s version, at Austin Friars, Cromwell’s city house, Cavendish has to recount the event in detail, he has to tell someone, he has to tell Cromwell everything:

‘George, make this story short, I cannot bear it.’ But George must have his say…

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall, Entirely Beloved Cromwell

Cromwell cannot bear it. He turns away, so he does not have to witness Cavendish’s grief – and to hide his own: “He looks at the wall, at the panelling, at his new linen fold panelling, and runs its fingers across its grooves.” This is the moment when he knows he will take revenge on all those who brought down his master.

And right now in 2023, I’m energised by the shock of seeing Wolsey’s quilts inventoried nearly 500 years ago. I shall carry on looking.