CW: This post contains references to the deaths of children.

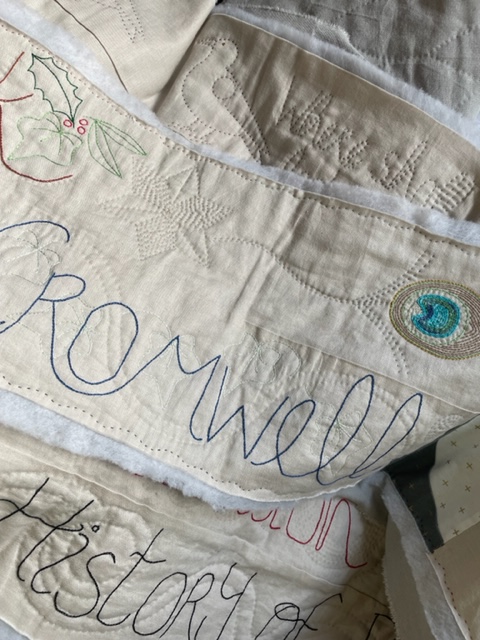

Thomas Cromwell’s daughters, Anne and Grace, are included in the Weepers series; and I felt that, as children, they should share a panel rather than be placed alone.

We know that Anne and Grace were once alive; they are both mentioned in the will Cromwell’s made in 1529. But Cromwell had to cross out the references to ‘my littill Doughters Anne and Grace’. They both died, young, later that same year. He had planned to leave them both money, to be passed to them when they reached ‘lawfull age or be maryed’. Poignantly, his will anticipated their deaths – the sweating sickness, the recent death of his wife Elizabeth, and high rates of child mortality being perhaps on Cromwell’s mind. The will therefore makes provision for the bequests to be passed on to his son Gregory, should his daughters be already dead at the time of his death.*

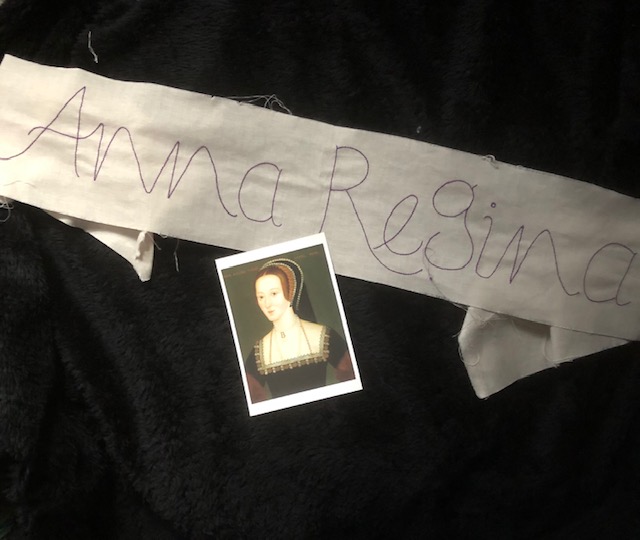

Hilary Mantel fictionalised Anne and Grace in the Cromwell Trilogy, and in so doing, she left a moving picture of Cromwell as father. In Mantel’s version, Anne is ‘a tough little girl […] she is no respecter of persons and her eyes, small and steady as her father’s, fall coldly on those who cross her.’ (Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain).

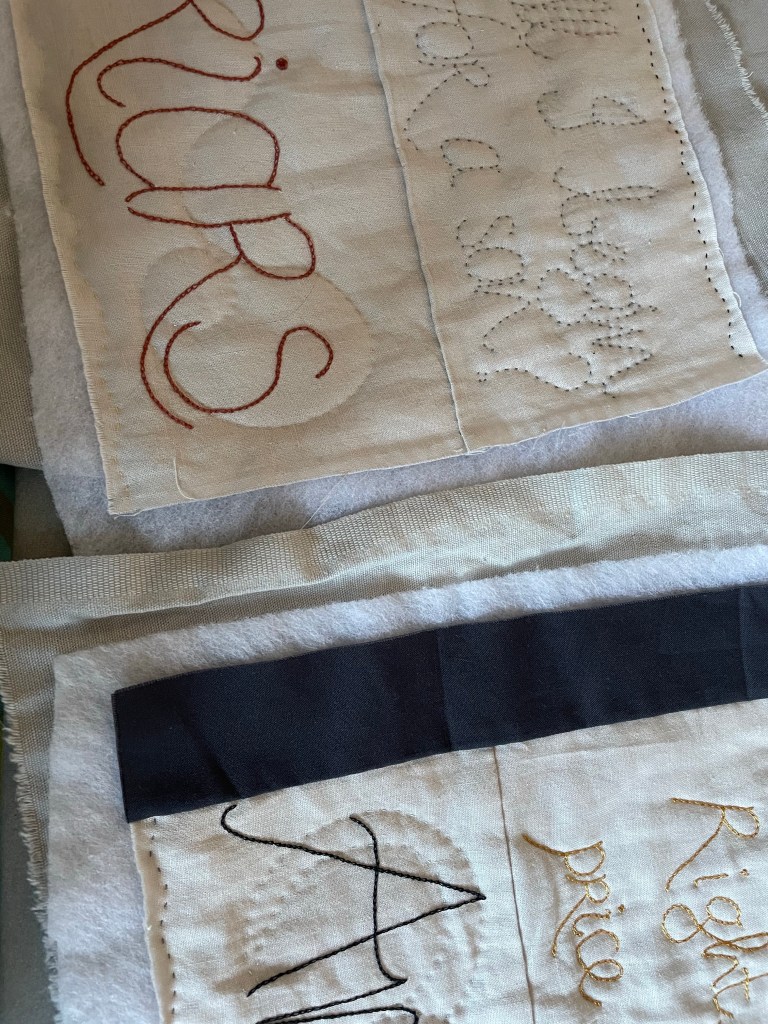

We learn that Anne has no interest in stitching, and that when she ‘applies to her needle, beads of blood decorate her work’. (The Mirror and the Light: The Bleach Fields). Anne is more interested in learning Greek, studying Latin, working with numbers. After her death, Cromwell would like her to be buried with the copybook in which she has written her name – Anne Cromwell, Anne Cromwell – over and over, but ‘the priest has never heard of such a thing. [Cromwell] is too tired and angry to fight.’ (Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain).

Because we are seeing events through Cromwell’s eyes, we know less about little Grace. When she dies, he thinks ‘I never knew her. I never knew I had her.’ (Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain).

Grace is a beautiful child, leading Cromwell to wonder whether she is actually his – after immersing himself in the flirtations and accusations of adultery at Court, he speculates that Lizzie, now dead, might have been with another man. Lizzie’s sister says no – Grace was his child. ‘But he cannot escape the feeling that Grace has slipped further from him. She was dead before she could be painted or drawn.’ (Bring Up the Bodies: Spoils).

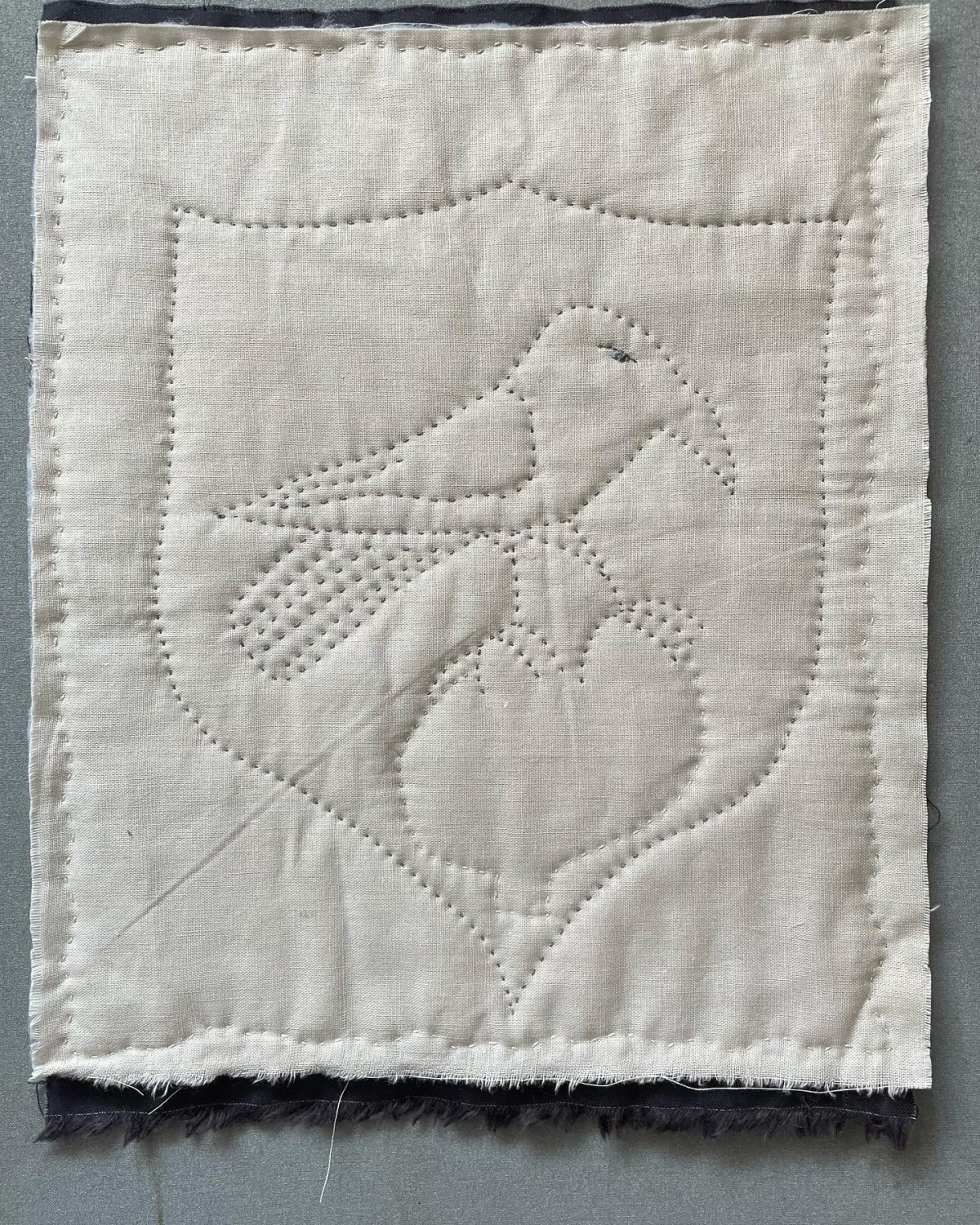

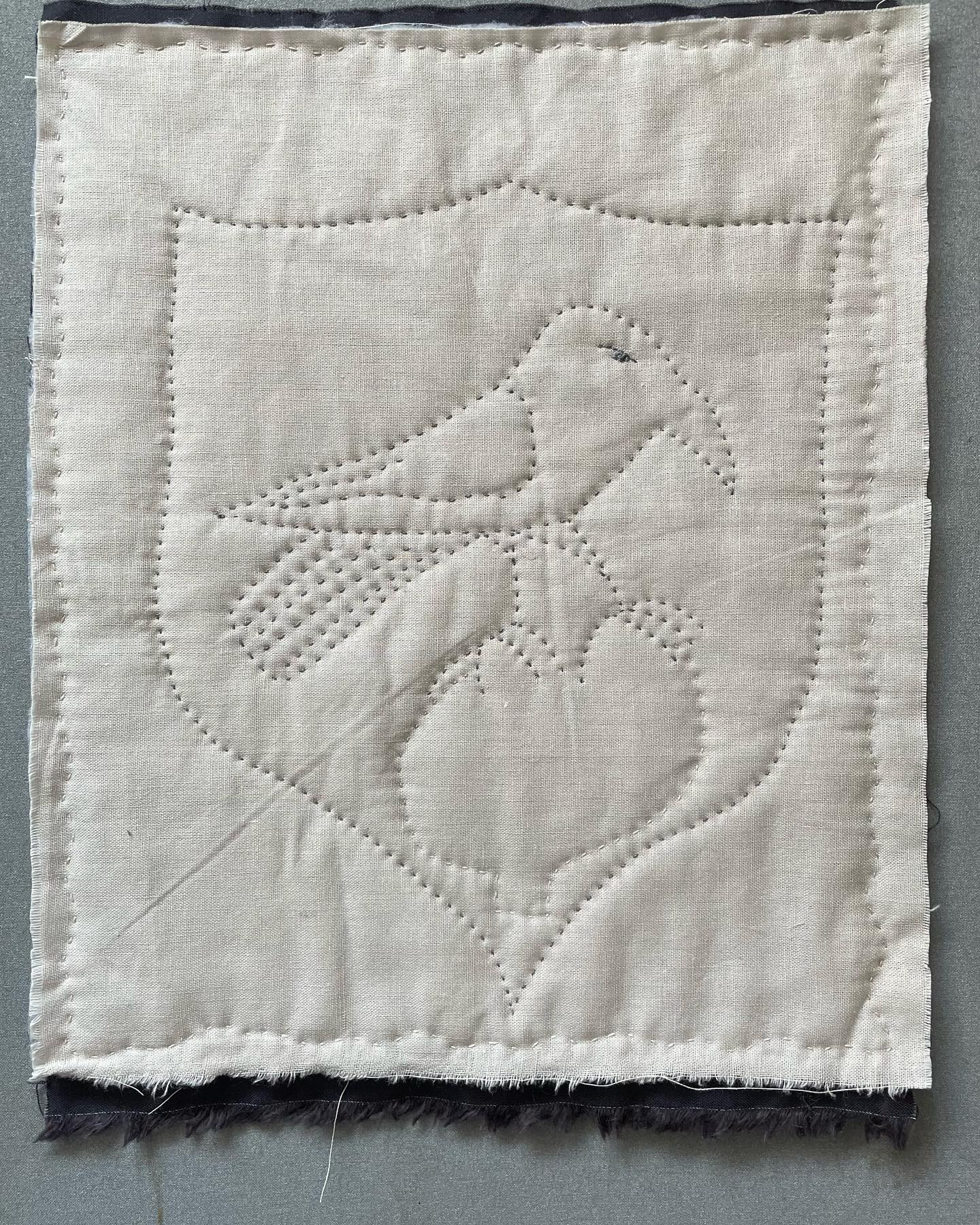

But during her short life, he makes wings out of peacock feathers for Grace to wear during the parish Christmas play, and she loves them. She doesn’t want to take them off, and he watches her, standing glittering in the firelight. And Cromwell keeps the wings for ten years after she has died, until they become ‘shabby, as if nibbled, and the glowing eyes dulled.’ (Bring Up the Bodies: Spoils).

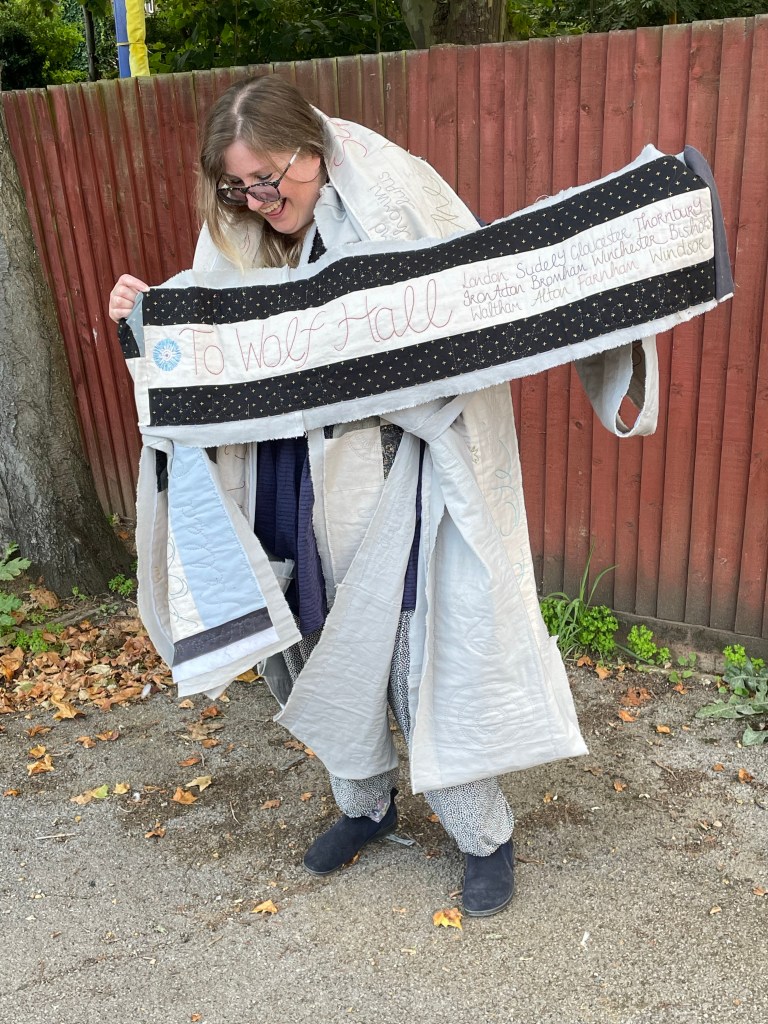

Photography: ©Michael Wicks

And when Cromwell reads his dead wife’s prayer book, it is the dead Grace’s hand he can see, reaching out to touch it. In life, she liked to look at the pictures; in death she does the same. As he turns a page, ‘Grace, silent and small, turns the page with him’. (Wolf Hall: Make or Mar).

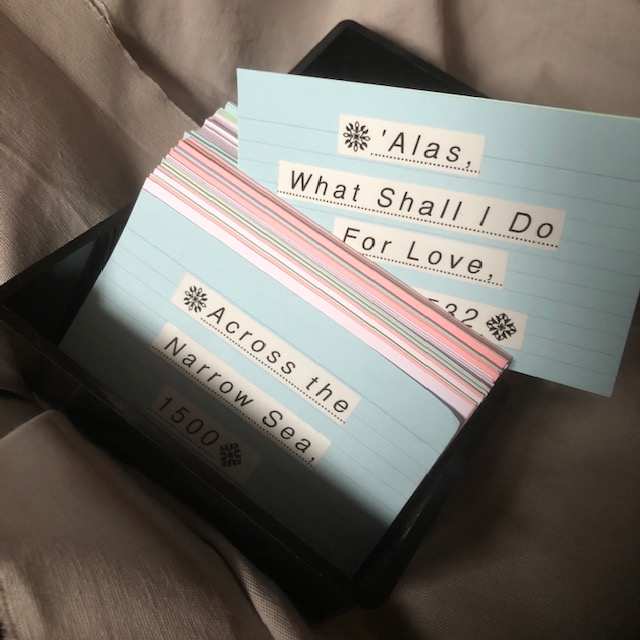

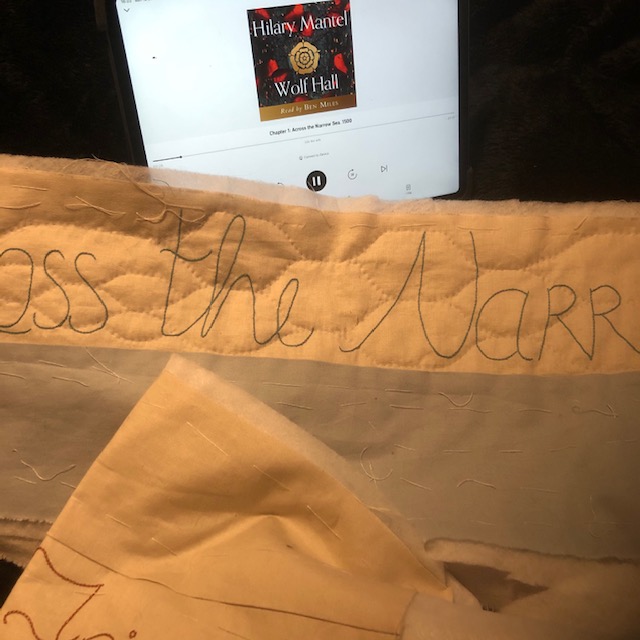

I realise now that I included references to Grace twice in the first Wolf Hall quilt – her peacock feather and her hand reaching for her mother’s prayer book – but there is no representation of Anne. Anne has the stronger personality on the page, we hear the noise of her feet, admire her determination, watch her assertive intelligence. Her family wonder ‘what London will be like when our Anne becomes Lord Mayor’. (Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain.

Anne’s omission from the first quilt now feels like a mistake. I can only explain it as a response to the grief in the text: listening to parts of An Occult History of Britain and Make or Mar while making the quilt was so painful that I had to move on from them. I expect I intended to return to them and add Anne at a later point. And now perhaps Anne’s absence from the quilt now represents her absence from Cromwell’s life.

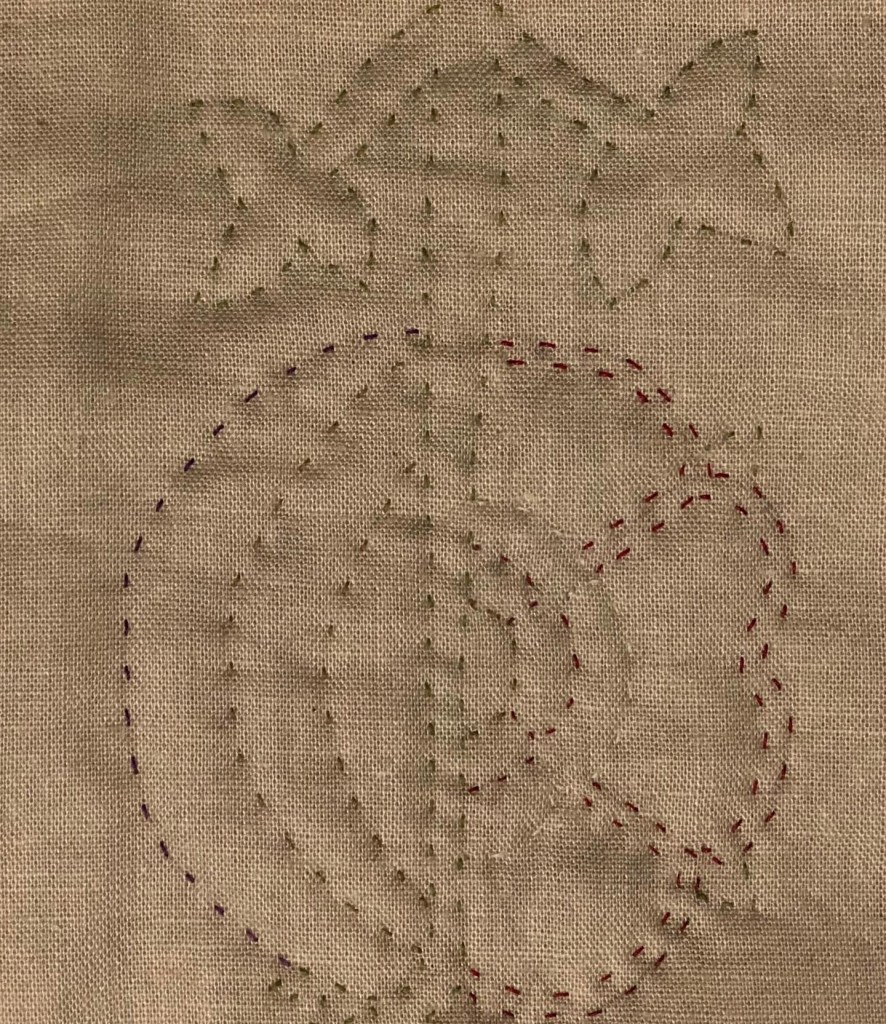

Anne is now presented as a weeper, wearing the cap with seed pearls that she liked to take off. Grace has not been painted or drawn, but she has been now stitched. Wearing her peacock feather wings.

* Cromwell’s will, including notes of the deletions, can be read in Life and Letters of Thomas Cromwell by Roger Bigelow Merriman, in two volumes, first published in 1902.