This is an extract from my paper written for and delivered at An Overflow of Meaning, the first international conference dedicated to the work of Hilary Mantel, held at the Huntington Library, California, in October 2021.

As a stitcher, specifically a quilter, I am particularly interested in the way in which Hilary Mantel described needlework in her Thomas Cromwell Trilogy. She differentiated between different types of stitchery, the people who stitched, and what they made, in a way that paid tribute to the hands that plied – and continue to ply – needles. After reading my analysis of her literary stitchery, Hilary wrote to me that “I cannot really sew”. I find that almost impossible to believe, given her respect for the act of stitching, but it is evidence of her astonishing talent as a writer.

They have brought out bolts of fine holland, velvets and grosgrain, sarcenet and taffeta, scarlet by the yard [1]

Anyone who reads the Cromwell Trilogy cannot fail to notice the centrality of fabric to the lives of those within it. There are incredibly descriptions of textiles of varying weights, weaves, fibres, and designs, as they are deployed to make up clothes, bedhangings, carpets, and napery. As Lucy Arnold has pointed out:

The language of the textile industry, the processes of weaving, dying, tailoring and adapting fabrics, saturates the novels as a well of talking about textuality, intertextuality and the signifying power of words. Cromwell returns repeatedly to tapestries which depict Biblical and mythological texts, and identifies flaws in the weave of fabrics which interrupt their ability to signify or signal authenticity […] Even written dispatches are sewn into their envelopes.[2]

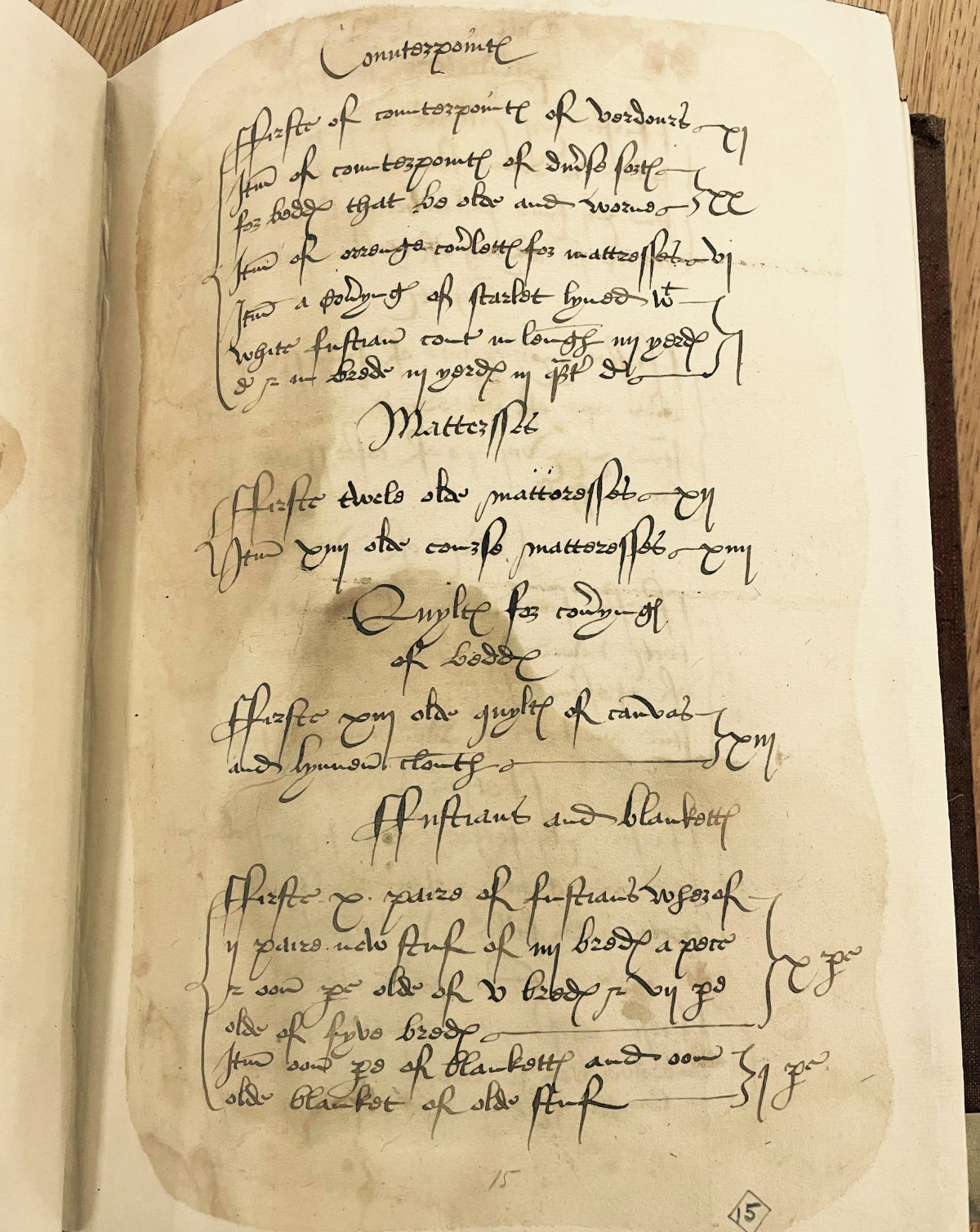

It helps having a protagonist who knows about textiles. Thomas Cromwell appreciates fabric and the processes that lie behind it: having a background in the cloth trade, how could he fail to do so? Cromwell’s appreciation allows the reader to enjoy many stitched items: the silk flowers given to Katherine by Henry; Jane Seymour’s Kingfisher sleeves; Anselma in the tapestry; Cromwell’s orange coat; Margaret Pole’s treasonous embroidery. My favourite is Cromwell’s own Quylte of Yelow Turquye Saten – a piece of bedding that once existed, according to his will. I have an expensive piece of Yelow Saten ready and waiting to be quilted.

The first time I read Wolf Hall back in 2009, I was struck by the amount of textile imagery. I remember noticing the recycling of Wolsey’s clothes on that reading, and drawing parallels with spotting an old and much-loved piece of fabric in a patchwork quilt:

The cardinal’s scarlet clothes now lie folded and empty. They cannot be wasted. They will be cut up and become other garments. Who knows where they will get to over the years? Your eye will be taken by a crimson cushion or a patch of red on a banner or ensign. You will see a glimpse of them in a man’s inner sleeve or in the flash of a whore’s petticoat.[3]

Two other phrases stuck with my stitching self, as they related to difficulties with a needle. One was the child Jo’s ‘awkward little backstitch which you would be hard-pushed to imitate’.[4] Her technique might not be all her mother Johane would desire, but its value is quickly recognised by Cromwell, who knows that even an unconventional stitch can come in useful, provided it can hold together, and promises her ‘I shall give you a present for sewing the cardinal’s letters’.[5] The other related to knitting:

He has never witnessed, or quite believed in, Lady Anne’s uncontrolled outbursts of temper. When he is admitted she is pacing, her hands clasped, and she looks small and tense, as if someone has knitted her and drawn the stitches too tight.[6]

I’m not a knitter, but I understand the difficulties of pulling a thread too tight when quilting and watching the fabric pull and pucker, knowing that at some date in the future, the thread will pull itself out, its starting knot emerging to the front of the quilt, insecure and hanging loose.

Neat Stitching … Who did this? [7]

It is the descriptions of the actual practice of stitchery that thread their way throughout the trilogy that fascinate me most. There is a clear understanding that needlework is labour, that it takes time, effort, and skill, that it is a deliberate act. George Cavendish knows this. As the Cardinal’s vestments and copes, ‘stiff with embroidery’, are confiscated he asks that the chests are lined:

with a double thickness of cambric. Would you shred the fine work that has taken nuns a lifetime?’ [8]

Mary Boleyn knows this. When she leaves Anne’s chamber to talk to Cromwell:

she’s brought her sewing with her, which he thinks is strange; but perhaps, if she leaves it behind, Anne pulls the stitches out.[9]

Bess Seymour, now Bess Cromwell, knows this. She brings Cromwell ‘news of needlework’, in which there is emotional as well as physical labour:

I was bidden to do a piece of work. One of the maids could have done it, but it was handed to me out of malice. It was something of Jane’s. Jane the queen, my sister, it was her girdle book, her little prayers. I was told, take this and pick the initials out. I said, I will not do it. I am Mistress Cromwell, not some servant.’ […] ‘The next thing I see, Katherine Howard is wearing it at her waist.’ [10]

Unpicking is never a pleasant task, it represents wasted effort and wasted time. There is an additional viciousness here: in an act of deliberate cruelty, Bess is expected to remove embroidery stitched for her dead sister, so that it can be given to another of the King’s loves. And for some people, sewing will never be pleasant whether the thread is going in or coming out. Cromwell’s young daughter Anne knows this. She does not enjoy learning needlework from her mother:

When Anne applies to her needle, beads of blood decorate her work. Liz says, she’d be better with a cobbler’s awl, except a cobbler wouldn’t be so chatty. He will not let his wife strike her; Anne cannot be faulted for diligence, and for the rest he feels she should not be faulted. ‘I suppose she will outgrow it,’ Liz says.[11]

Cromwell’s unknown daughter Jenneke, on the other hand, having learned perhaps from Anselma, is a proficient stitcher. Before we meet her in person, before Cromwell knows who she is, he is commenting on her ‘neat stitching’:

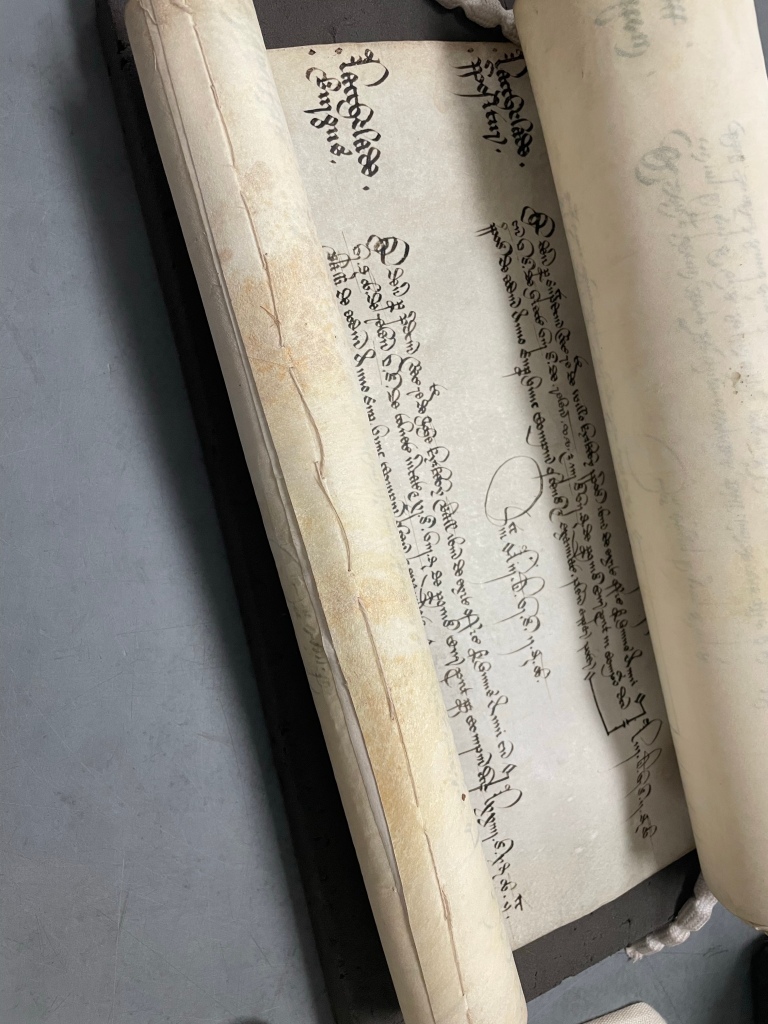

As they speak he is unrolling the jerkin. With a shake, he turns it inside out, and with a small pair of scissors begins to split open a seam. ‘Neat stitching… who did this?’ The boy hesitates; he colours. ‘Jenneke.’ He draws out from the lining the thin, folded paper.[12]

Thomas Cromwell knows that stitching isn’t just something that happens, there is a person (in his world, usually a woman) behind it, and that it is a conscious act on the part of the person who plies the needle. He knows this because he recognises the vital importance of the cloth trade to England’s economy and to the people who work within it.

She has been sewing – or rather unsewing [13]

In Cromwell’s world, sewing is never neutral. What is sewn, how it is stitched, and who threads the needle all have an impact on the cut of the cloth. Emblems and badges are embroidered so, as queens change, their supporters are kept busy unpicking and stitching new emblems to reflect the current state of the king’s matrimonial affairs. The blackwork embroidered by Henry’s first queen is long gone by the time of his third; now his shirts ‘are stitched by paid and proficient hands, with lions and laurel crowns’.[14] The politics of pregnancy are played out by the letting out and taking in of bodices.

Cromwell, who ‘of your gentleness… interest[s] yourself in the work we women do’,[15] hopes that Honor Lisle will incriminate herself with a letter to or from Reginald Pole hidden in her sewing box.[16] She is not caught out, but Pole’s mother is caught stitching treasonous embroidery. Margaret Pole’s hands might look innocent enough as she ‘takes a neat loop of her thread and slips her needle into the cloth’,[17] but her stitching demeanour is far from placid as ‘her hawk’s profile is lowered over her work, as if she is pecking it’.[18] Her stitched garden contains hopes of an alliance between the Princess Mary and the Pole family.

Cromwell, of course, is wise to what she is stitching and considers it ‘useful to have the evidence stitched together. “I hope that when that cloth is finished,” he says, “the family will protect it from the light.”’ [19] It is, ultimately, stitched evidence that Cromwell is able to present – wordlessly [20] – to Parliament: ‘a figured vestment found in the possession of Margaret, Countess of Salisbury. It quarters the arms of England with a pansy for Pole and a marigold for the Lady Mary, signifying their union; between them grows a Tree of Life […] He says, I always maintained that embroidery would get her into trouble.’ [21]

Every hand that could hold a needle would go to work [22]

A close reading of the three novels shows that the stitching activities are as various as the (mostly) women who undertake them and the textiles to which they contribute:

Sail-making: Helen Barre

Utility stitching: Jenneke; Hans Holbein (metaphorical)

Backstitch (awkward): The child Jo

Shroud-making: Mercy (assumed); Cromwell, Jane Rochford, Thomas Wyatt (metaphorical)

Clothes-making: Queen Katherine; Anne Boleyn; Mary Boleyn; Jane Seymour; Liz (not explicit); Cromwell (implied)

Clothes recycling: Mercy; Johane; Bet; Kat; Princess/Lady Mary

Clothes repair: Lady Bryan; Katherine Howard (hemming); Margaret Douglas (hemming)

Patchwork: Liz

Quilting: Liz

Embroidery: Queen Katherine; Jane Seymour; Anna of Cleves; Mary Boleyn; Liz; Helen Barre; Margaret Pole; Bess Darrell; Honor Lisle; unnamed nuns; Mercy, Anne/Grace Cromwell (possible)

Blackwork embroidery: Queen Katherine; Liz

Silk work: Liz

Braiding: Liz

Unpicking: Jo; Anne Boleyn; Mary Boleyn; Bess Seymour; Jane Seymour’s ladies

Unspecified sewing: Johane; Kat; Anne Cromwell; Queen Katherine; Anne Boleyn; Jane Seymour; Anna of Cleves; Thomas Seymour’s wife; Anne Boleyn’s ladies; Jane Seymour’s ladies; Lady Shelton

Untangling of thread: Cromwell

Eye surgery using needle (dog): Cromwell

Both in the novels and in life, it should not be assumed that because someone can work in one type of sewing, they will be proficient at all. If, for example, you quilt, you are likely to be asked to repair a dropped hem on somebody’s skirt. If you embroider, you might be asked to take in a dress. If you are a dressmaker, you might be asked to finish off someone’s abandoned cross stitch. But this results from a misunderstanding of the difference in technique, skill, and specialism. Patchworkers are not necessarily quilters, who are not necessarily embroiderers, who are not necessarily tapestry weavers; who are not necessarily dressmakers, and so on. One of the many pleasures of the Cromwell Trilogy is Mantel’s differentiation of stitchery. From sail-making to silk embroidery, the needlework is various, and highly specialist. It is not a neutral activity, but is weighted with class, expectation, and intent.

The most able stitcher, in terms of the number of techniques in which she is proficient, is Elizabeth Cromwell. Liz uses patchwork and quilting techniques in the making of Twelfth Night costumes; she embroiders cushions for her home and narrows that embroidery down to blackwork when making shirts for Gregory (and, while the text is silent about this, perhaps we can assume she has stitched said shirts); she does silk work, including braiding, and, like many experienced stitchers, she has the muscle memory to work without thinking:

Once he had watched Liz making a silk braid. One end was pinned to the wall and on each finger of her raised hand she was spinning loops of thread, her fingers flying so fast he couldn’t see how it worked. ‘Slow down,’ he said, ‘so I can see how you do it,’ but she’d laughed and said, ‘I can’t slow down, if I stopped to think how I was doing it I couldn’t do it at all.’ [23]

And in an echo of Cromwell saying he would – deliberately – leave his needle in if he were stitching the king’s shirts,[24] Liz – unconsciously – stores her needle in a piece of embroidery, a bad habit shared by so many stitchers, and leaves behind a ghost in her stitching:

There is a cushion over on which she was working a design, a deer running through foliage. Whether death interrupted her or just dislike of the work, she had left her needle in the cloth. Later, some other hand – her mother’s, or one of her daughters’ – drew out the needle; but around the twin hole it left, the cloth had stiffened into brittle peaks, so if you pass your finger over the path of her stitches – the path they would have taken – you can feel the bumps, like snags in the weave.[25]

Liz’s skill with needle and thread is such that her hands can move while she talks or thinks of other things; her craft has become part of her. That is not to say that her work is without intent or that it is easy. Her confidence in the tiny movements of textile work is brought about from long experience and repeated practice.

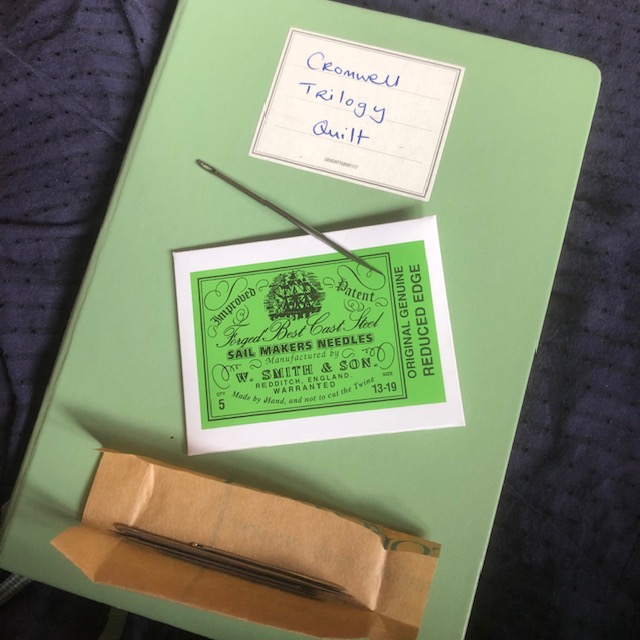

Helen Barre unwinds the thread of her tale [26]

The different types of stitchery are exemplified in Helen Barre, and that is why this paper is named after her. When we first meet Helen, she explains that, in about 1530, she was ‘stitching for a sailmaker’ somewhere in Essex, maybe around Tilbury (where her first husband disappeared).[27] Cromwell notices that Helen’s hands are ‘skinned and swollen from rough work’.[28] This is unsurprising: while I am not an expert in antique sailmaking tools, I can confirm that from a 21st century stitcher’s perspective, sailmaking continues to be rough work. Sailmakers’ needles are terrifying things: long, thick, and lethal. You would not want to get on the wrong side of one. To get your needle through heavy canvas or to attach rope securely, a finger thimble would be useless; you need a Sailmaker’s Palm: a leather strap that goes around your hand with a metal pad that fits in your palm. Then you can employ all your strength to push your needle through. I have a Sailmaker’s Palm in my sewing basket, but it is far too big for my hand. I suspect these tools are designed for larger and stronger hands than mine, and indeed Helen’s.[29]

Helen is destined for finer fabrics. As with his habit of dressing and re-dressing queens, when she first arrives at Austin Friars, Cromwell ‘mentally… takes her out of cheap shrunken wool and re-dresses her in some figured velvet he saw yesterday, six shillings the yard.’ [30] Later, when Helen prepares a room for the visit of the Princess Mary, he watches her pleasure at the opportunity ‘to handle the fine stuff and have a brigade of cushions at her command.’ [31] And as Helen learns to ‘handle the fine stuff’, the nature of her stitching changes. As the wife of Rafe Sadler, a sailmaker’s needle is no tool for her gentlewoman’s hand. By 1536, she is working on fine embroidery; her thread is now fine silk rather than coarse twine or rope, her needle is thinner, shorter, and sharper. She sews for Dorothea Wolsey ‘a kerchief of fine linen […] worked with the three apples of St Dorothea, and with wreaths, sprigs and blossoms, the lily and the rose’,[32] in ‘loving stitches… to give pleasure to a stranger’.[33] The stranger – Dorothea – rejects both the loving stitches and Cromwell himself. When Cromwell returns to London, with the embroidered kerchief, he passes it to Rafe to give back to Helen.[34]

Dorothea’s rejection of Cromwell is shocking enough on its own, but for a stitcher, with a keen awareness of the time and effort that went into those loving stitches, the rejection of Helen’s work is an additional blow. Perhaps it would have been kinder for Cromwell – or perhaps Rafe – to keep the kerchief for himself, rather than let Helen know it was not wanted. I noted, with relief, when watching the stage version of The Mirror and the Light that Helen’s embroidery was absent when Cromwell went to see Dorothea. But the casting of Umi Myers in the dual role of both Helen and Dorothea is a subtle reminder that these two women are linked by stitch.[35]

My fingers are kept supple by plying my needle [36]

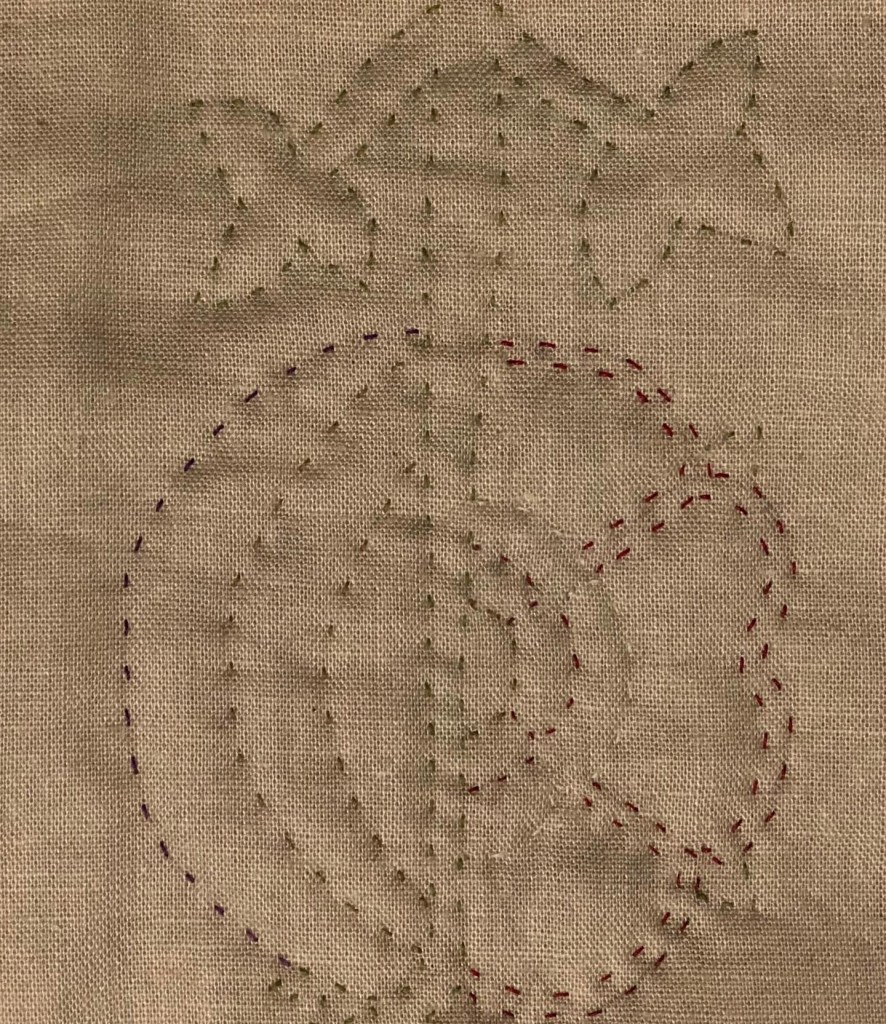

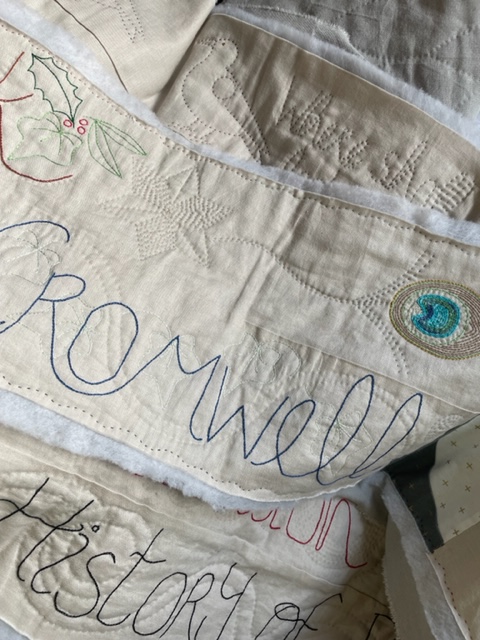

It is unsurprising that a trilogy of novels that pay so much respect and attention to the act of stitching should have a particular resonance for anyone who works in textiles, and, in my case, form the inspiration for a large ongoing sewing project (or should that be projects?). My first Cromwell-related quilt was made in 2014; since then there have been numerous projects. As I write, I am looking at the first 30 feet of my current Cromwell Narrative Cloth – a piece that tells the story of the Trilogy in chronological order. Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy is a constant source of inspiration, and now I cannot think that I will ever stop stitching it.

[1] Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall: Visitation (London: Fourth Estate, paperback edition, 2019) , p.50.

[2] Lucy Arnold, Reading Hilary Mantel: Haunted Decades (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), pp.166-167.

[3] Wolf Hall: Entirely Beloved Cromwell, pp.265-266.

[4] Wolf Hall: Entirely Beloved Cromwell, p.239.

[5] Wolf Hall: Entirely Beloved Cromwell, p.259.

[6] Wolf Hall: ‘Alas, What Shall I Do For Love?’, p.373.

[7] Wolf Hall: Arrange Your Face, p.304.

[8] Wolf Hall: Visitation, p.50.

[9] Wolf Hall: Entirely Beloved Cromwell, p.203.

[10] The Mirror and the Light: Magnificence (London: Fourth Estate 2019), p.788.

[11] The Mirror and the Light: The Bleach Fields, p.420.

[12] Wolf Hall: Arrange Your Face, p.304.

[13] Wolf Hall: Devil’s Spit, p.501.

[14] The Mirror and the Light: Vile Blood, p.334

[15] The Mirror and the Light: Salvage, p.193.

[16] The Mirror and the Light, Magnificence, p.766.

[17] The Mirror and the Light: Salvage, p.194.

[18] The Mirror and the Light: Salvage, p.106.

[19] The Mirror and the Light: Wreckage II, p.198.

[20] See Susan Higginbotham, Margaret Pole: The Countess in the Tower (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2017), p.129.

[21] The Mirror and the Light: Ascension Day, p.665.

[22] The Mirror and the Light: Magnificence, p.720.

[23] Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies: The Black Book (London: Fourth Estate, paperback edition 2019), pp.286-287.

[24] Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain p.92.

[25] The Mirror and the Light: Salvage, p.65.

[26] Wolf Hall: Anna Regina, p.419.

[27] Wolf Hall: Anna Regina, p.420.

[28] Wolf Hall: Anna Regina, p.419.

[29] Traditional Sailmaking is now officially considered an Endangered Craft with between just 21 and 50 professional makers left in the UK. As the Heritage Crafts Association note, ‘Many people would like to have sails made traditionally, but very few are willing to pay the price of someone working eight hours a day hand-sewing’. Red List of Endangered Crafts: Sailmaking, Heritage Crafts Association website, https://heritagecrafts.org.uk/sail-making/ [accessed 1 October 2021].

[30] Wolf Hall: Anna Regina, p.419.

[31] The Mirror and the Light: Salvage, p.149.

[32] The Mirror and the Light: The Five Wounds, p.282.

[33] The Mirror and the Light: The Five Wounds, p.289.

[34] The Mirror and the Light: The Five Wounds, p.290.

[35] The Mirror and the Light, Royal Shakespeare Company and Playful Productions, first performed at the Gielgud Theatre London on 23 September 2021.

[36] The Mirror and the Light: Magnificence, p.726.