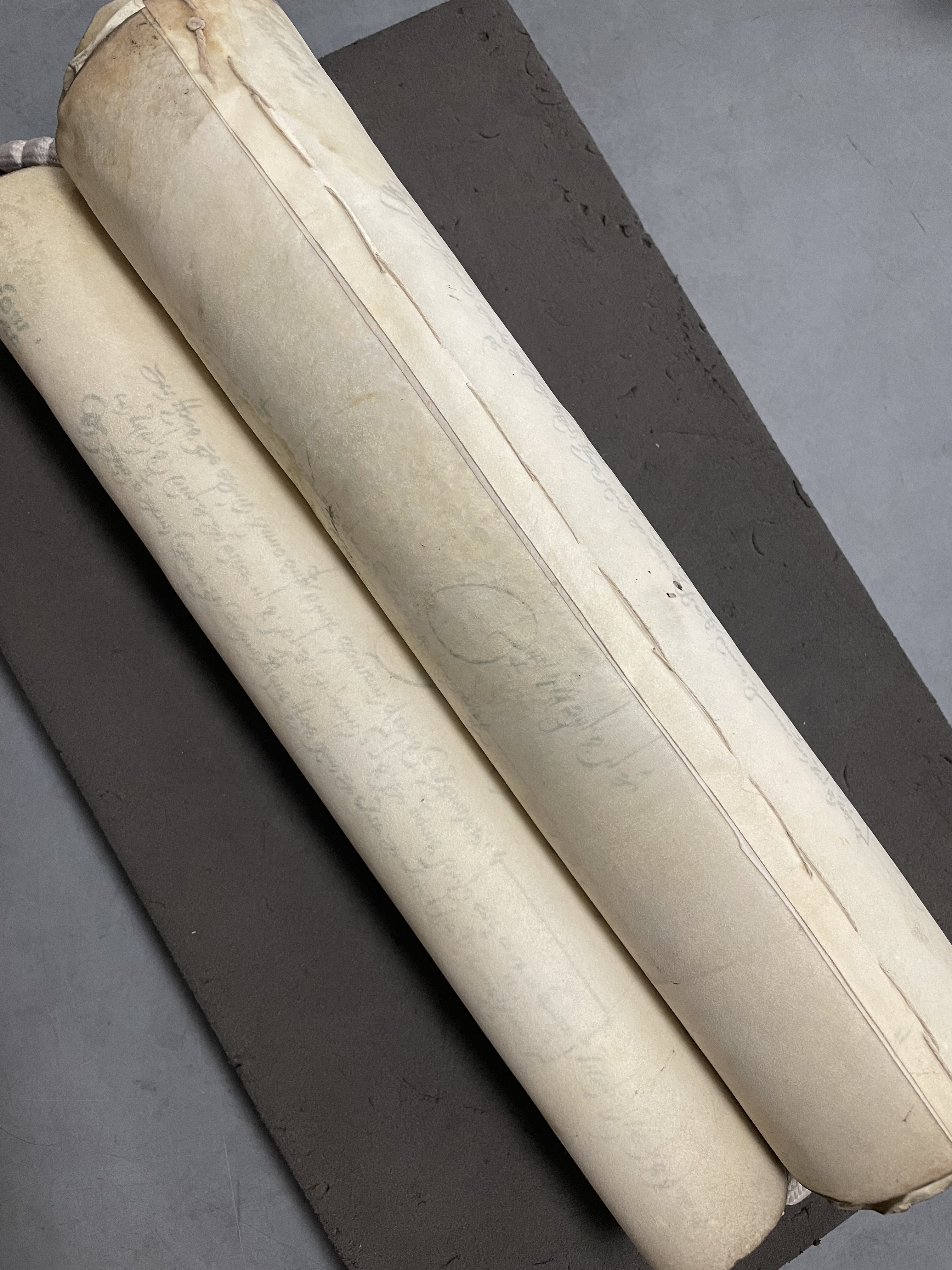

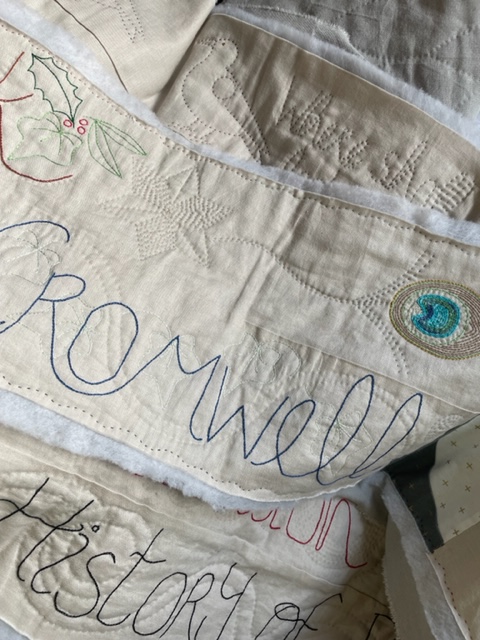

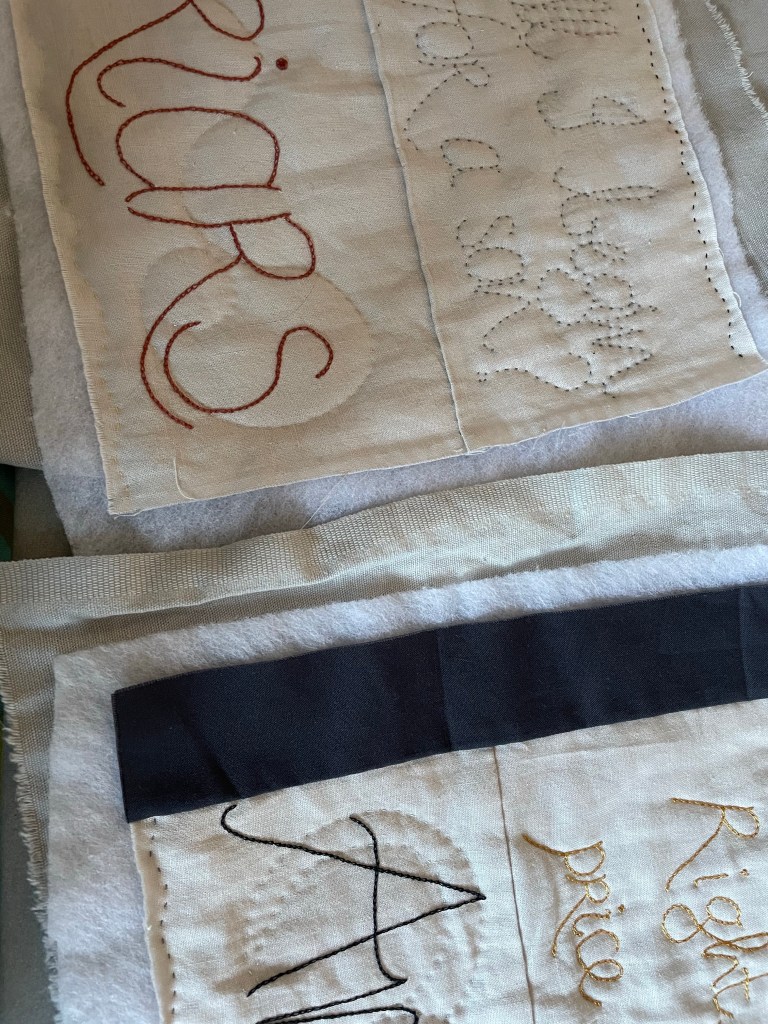

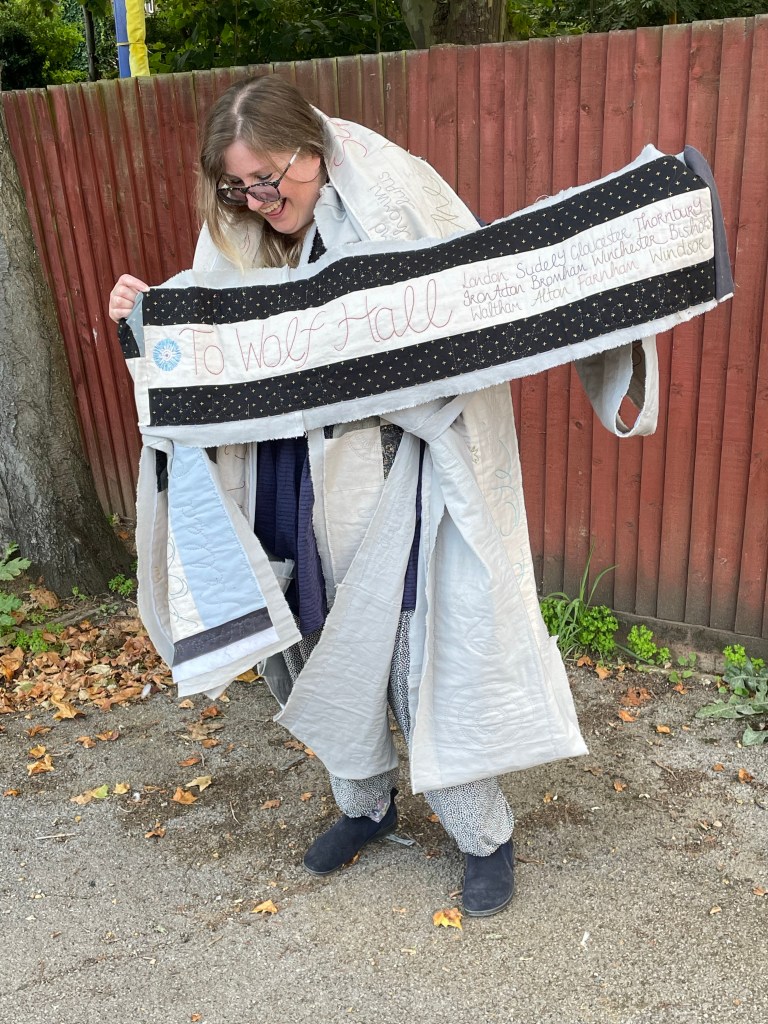

Since my earlier post about commemorating the dead, and my explorations of weeper tombs, I have started stitching characters from Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy who are to be included in my Weepers series. It’s quite an intense process: sketching out ideas, reminding myself of small details in the text, noting down some of their words, or what is said of them.

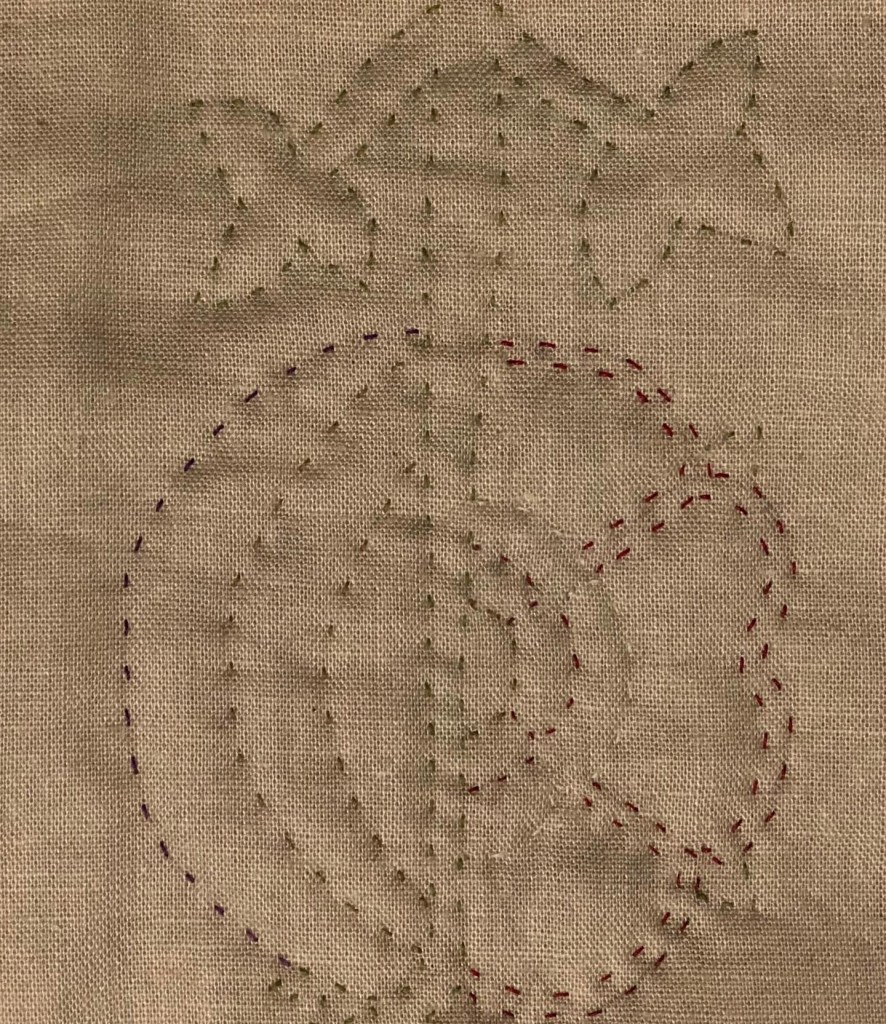

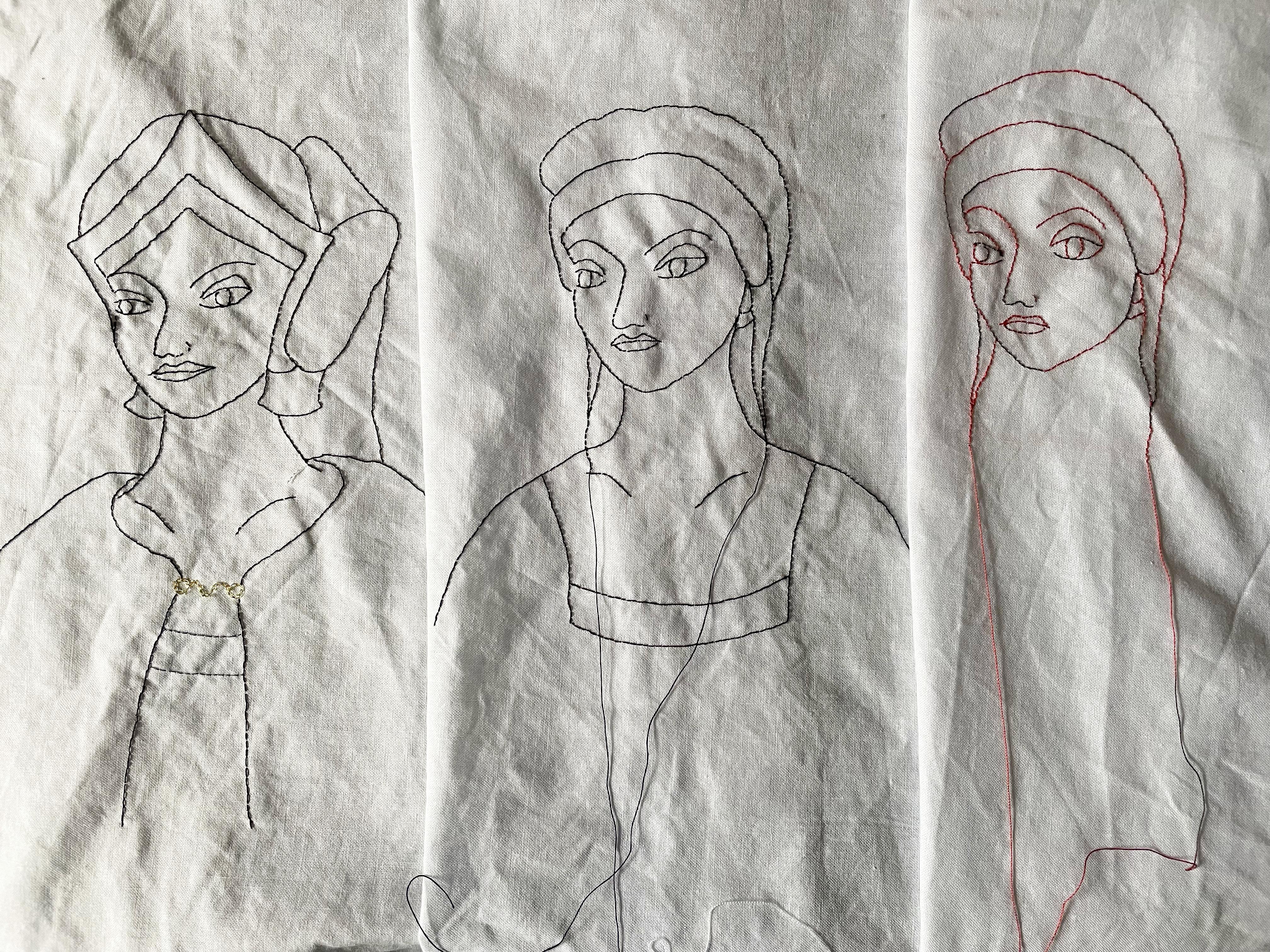

Once I get to the stitching stage, I start with outlines. Then I add a little detail. Then the figure sits for a while, waiting. Eventually, once I feel that the future is ready, I draw in a face. I am yet to add any text – and yet to decide exactly how I will do this; and I am still considering whether to also add objects relating to each figure. Maybe, maybe not.

Yesterday morning I finished the initial work on Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth Wykys. We know very little about the real Elizabeth Wykys, but in fiction, Hilary Mantel conjured a memorable character, and chose to give her great proficiency in textiles. In the Play Script, she wrote:

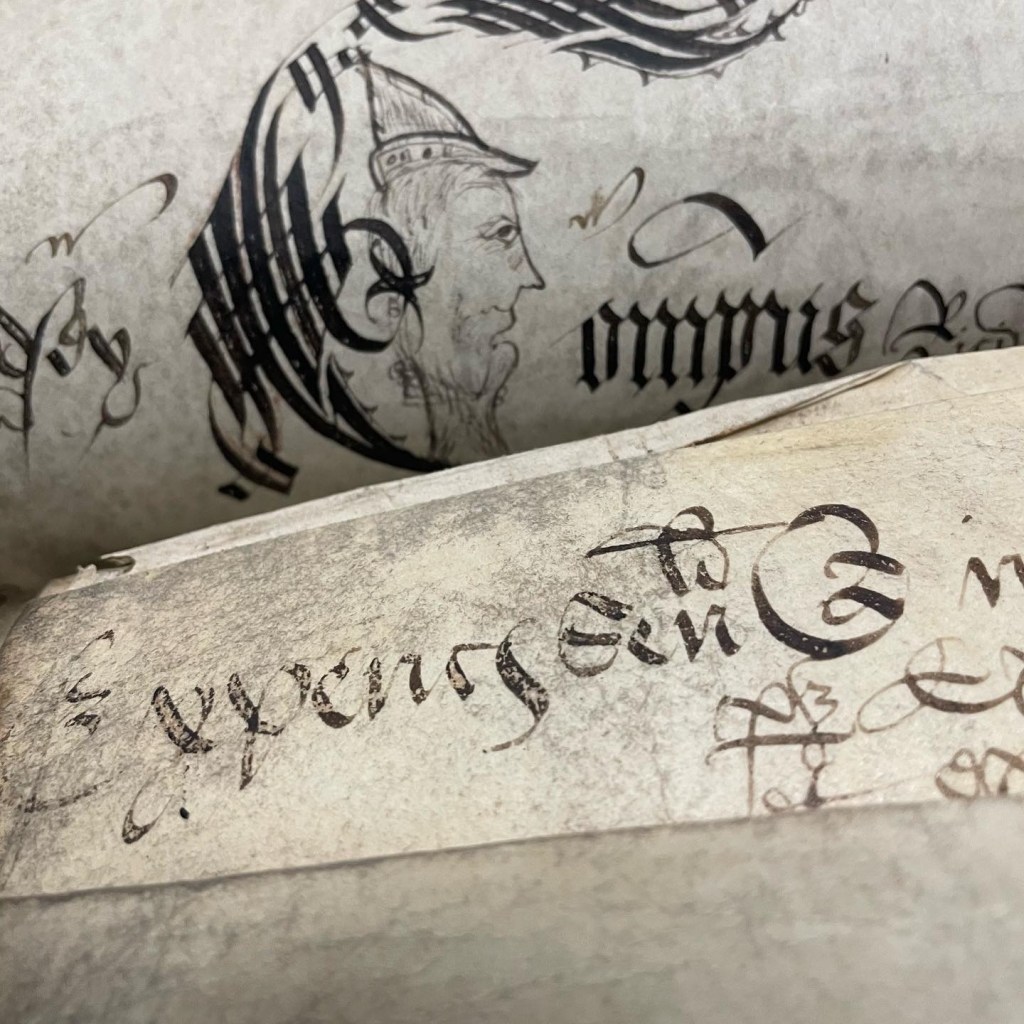

We know nothing about you, so we can only say, ‘women like you’. City wives were usually literate, numerate and businesslike, used to managing a household and a family business in cooperation with their husbands. In Wolf Hall, I make you a ‘silk woman’, with your own business.

Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies. Adapted for the stage by Mike Poulton. From the novels by Hilary Mantel. (Notes on characters by Hilary Mantel)

My stitched Liz took a while to emerge. Although I quilted her outlines some weeks ago, she wasn’t fixed. For a while, I thought she might turn out to be Jenneke. I stitched another set of outlines, but my second attempt turned out – very definitely – to be Helen Barre. Liz was difficult to capture, as Cromwell himself finds after her death. He wishes Hans Holbein had painted her while she was alive, as in his memory:

even Liz’s face is a blurred oval beneath her cap.

Hilary Mantel, The Mirror and The Light: Augmentation, London, Autumn 1536

In the Cromwell Trilogy, Liz represents the happiness of Cromwell’s private life and domestic stability during his marriage. She and Thomas enjoy each others’ company, they relax together, and make each other laugh:

‘Men say’, Liz reaches for her scissors, ‘”I can’t endure it when women cry” – just as people say, “I can’t endure this wet weather.” As if it were nothing to do with the men at all, the crying. Just one of those things that happen.’

‘I’ve never made you cry, have I?’

‘Only with laughter,’ she says.

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall: An Occult History of Britain, 1521-1529

Liz plays another vital role in my reading of the Cromwell Trilogy: that of a very skilled maker. My analysis of the practice of stitching in the Trilogy indicates that she is the most proficient stitcher in terms of the number of techniques she uses. At various points in the novels, we observe her working with fabric and thread – she embroiders Gregory’s shirts with a black-work design (and I think it is reasonable to assume she has made said shirts); she makes costumes for the Christmas celebrations, using quilting and patchwork; professionally she is a silk woman, making braids, tassels, and net cauls. Less successfully, perhaps, she also teaches her daughter Anne to sew, but Anne struggles with a needle, asserting her own interests instead.

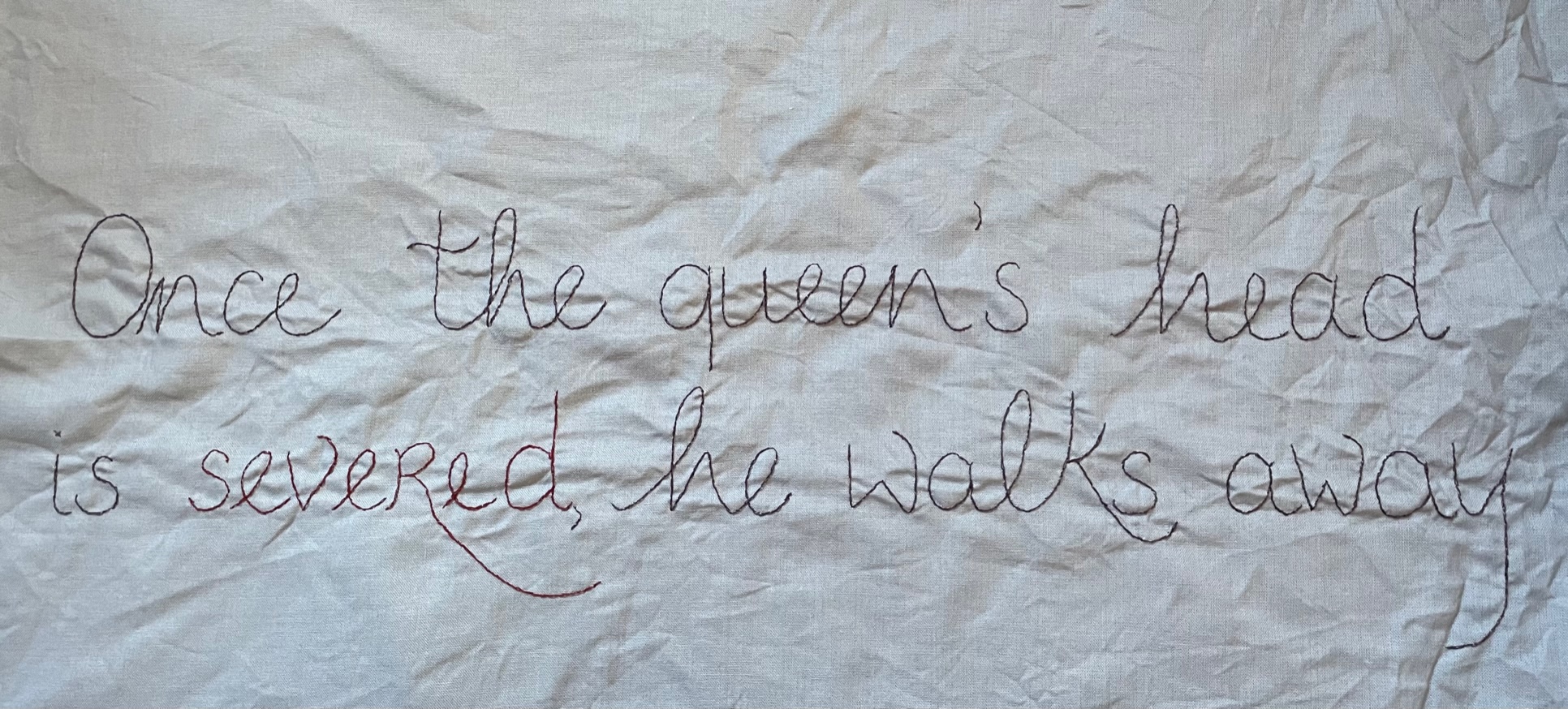

After her death, Cromwell finds a cushion she had started embroidering. She didn’t finish the piece but she left her needle in the fabric. Cromwell can feel the path Liz’s stitches would have taken, the bumps that have been left by her abandoned needle.

Like many experienced stitchers, Liz has the muscle memory to work without thinking. When Cromwell asks her to slow down so he can see how she spins loops of thread for a braid, she laughs.

“I can’t slow down, if I stopped to think how I was doing it I couldn’t do it at all”.

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies: The Black Book, London, January-April 1536

While her work may be automatic, it is not without intention. Liz’s confidence in the tiny movements of textile work is brought about through long experience and repeated practice.

I hope my representation does justice to the character that Hilary created. Liz is now hanging up in my studio next to Cromwell himself, waiting to become part of a larger piece of work.