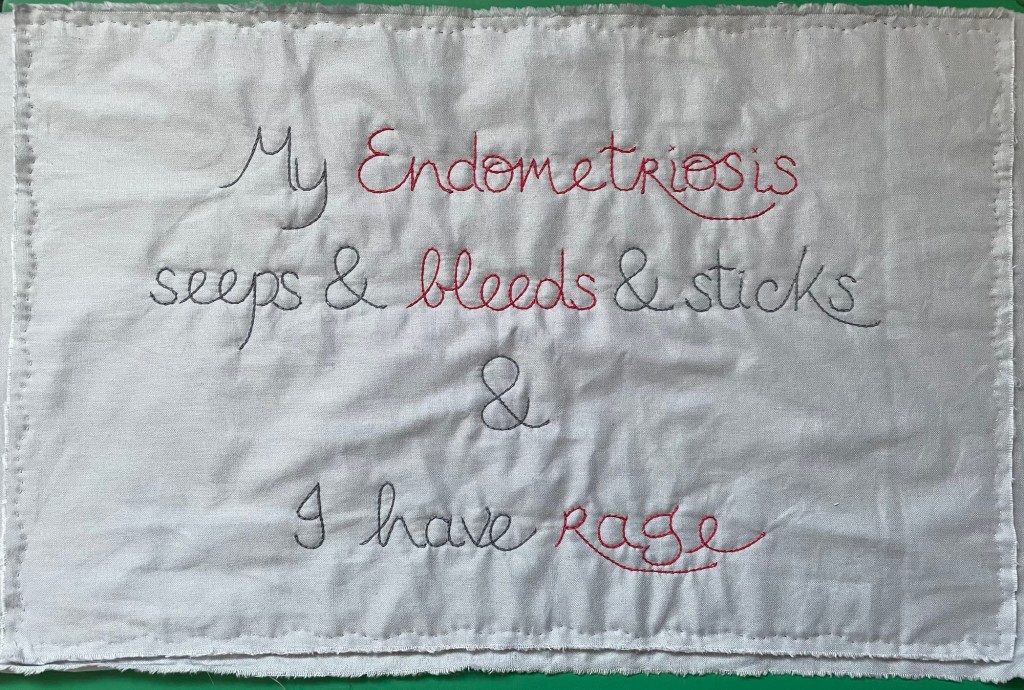

This piece is about chronic pain – specifically endometriosis – and also covers issues of fertility, infertility, and surgery. It was originally posted on The Thread of Her Tale, my “Show your workings” site, where it resonated with many people, so it is being republished here, with a couple of minor amendments.

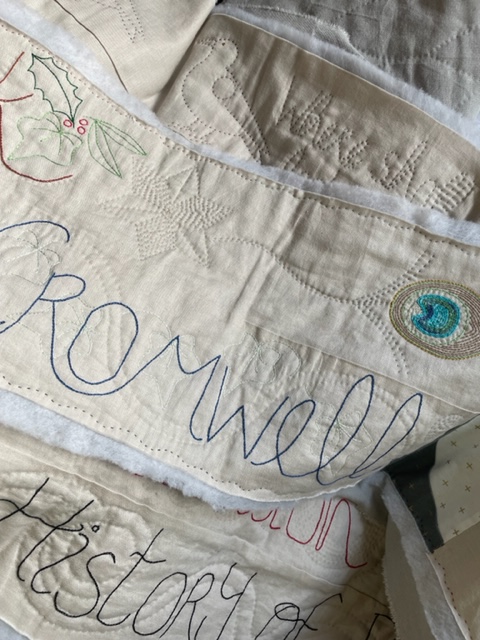

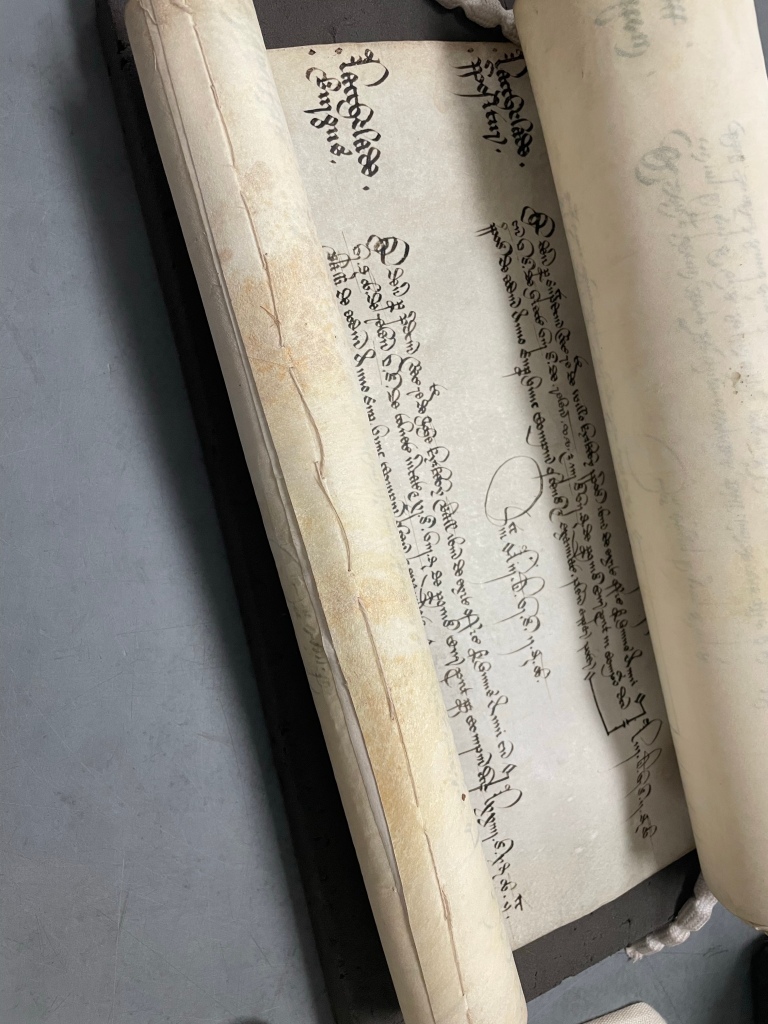

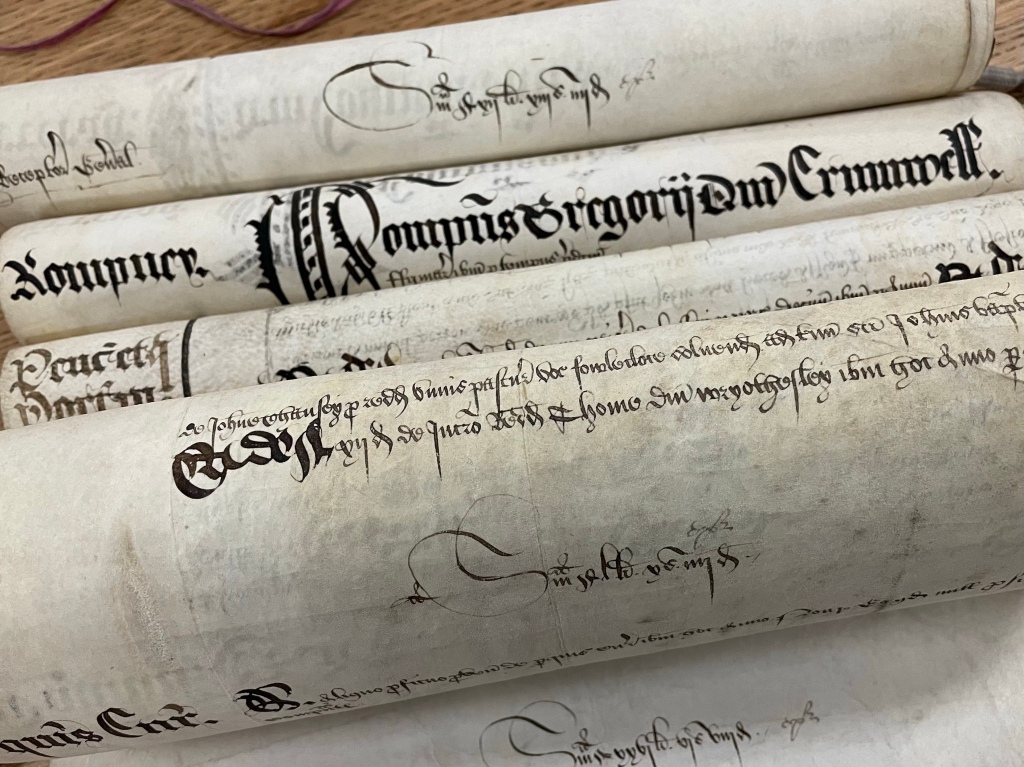

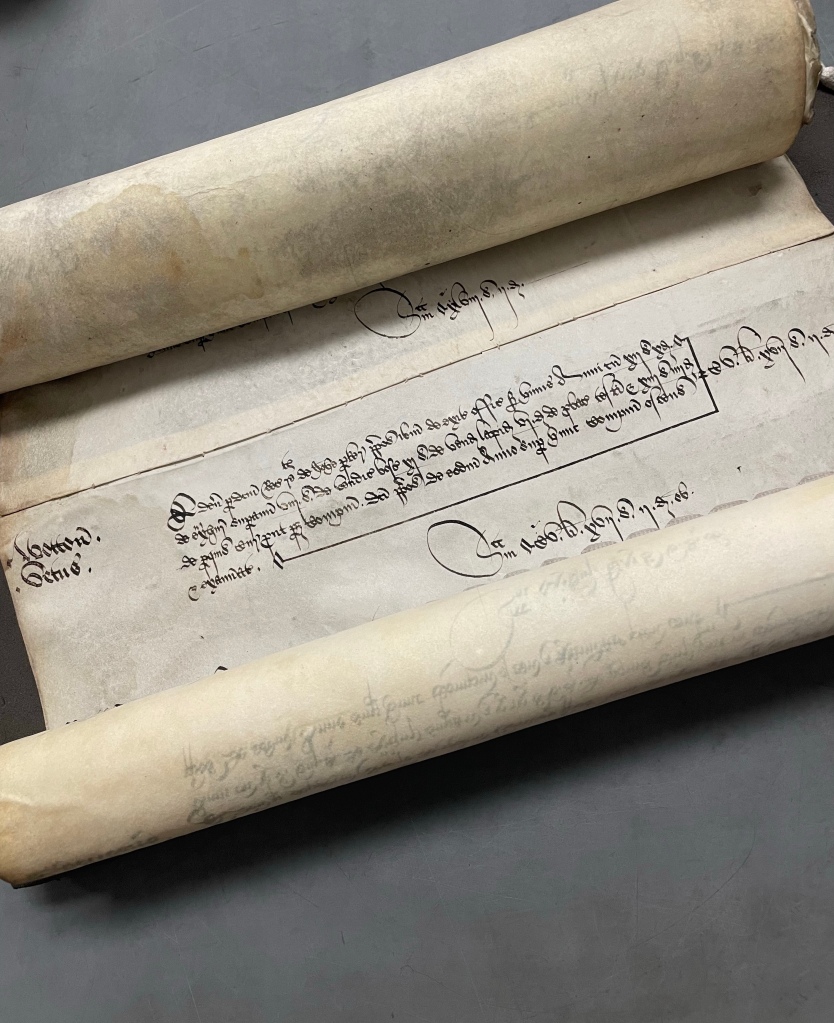

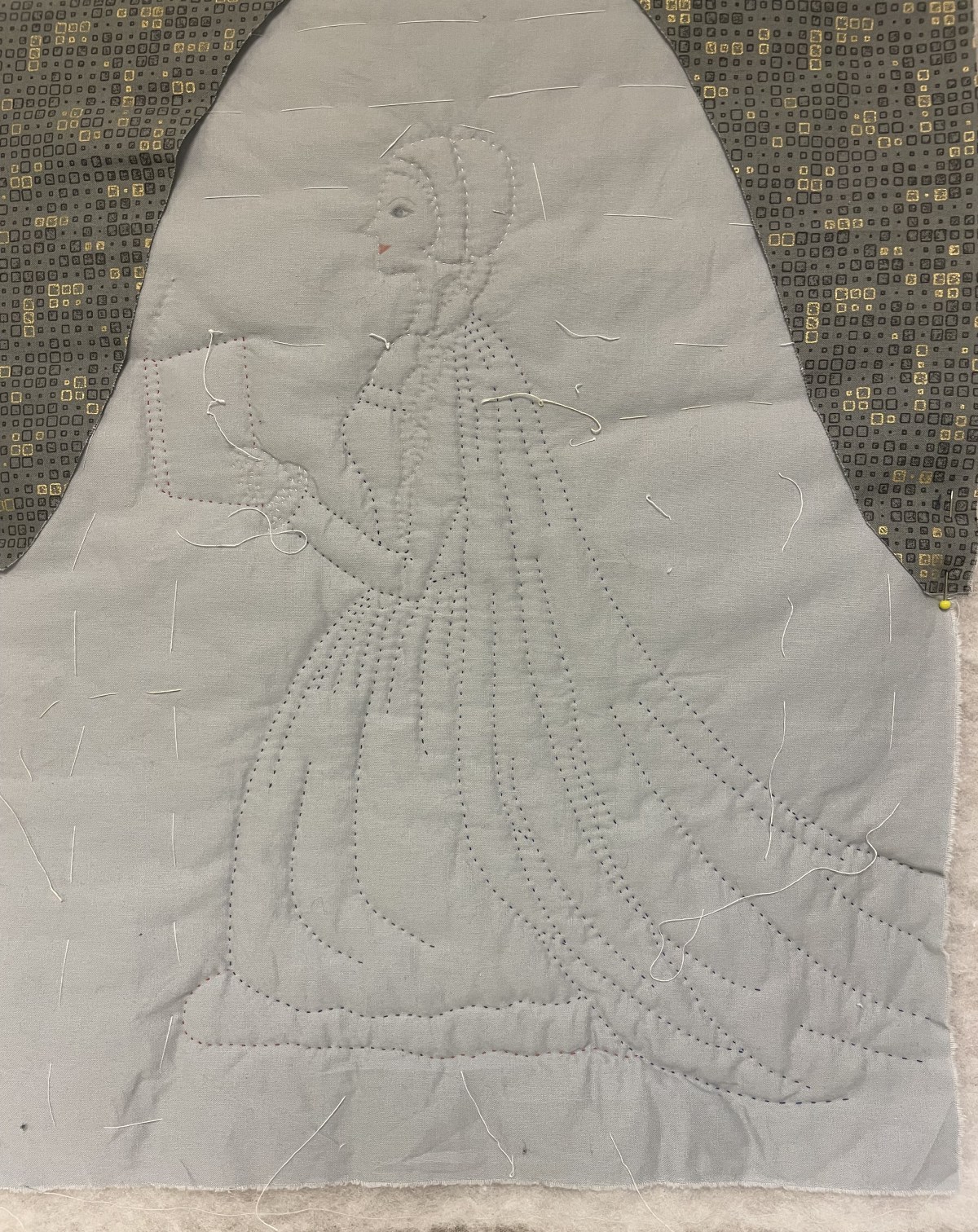

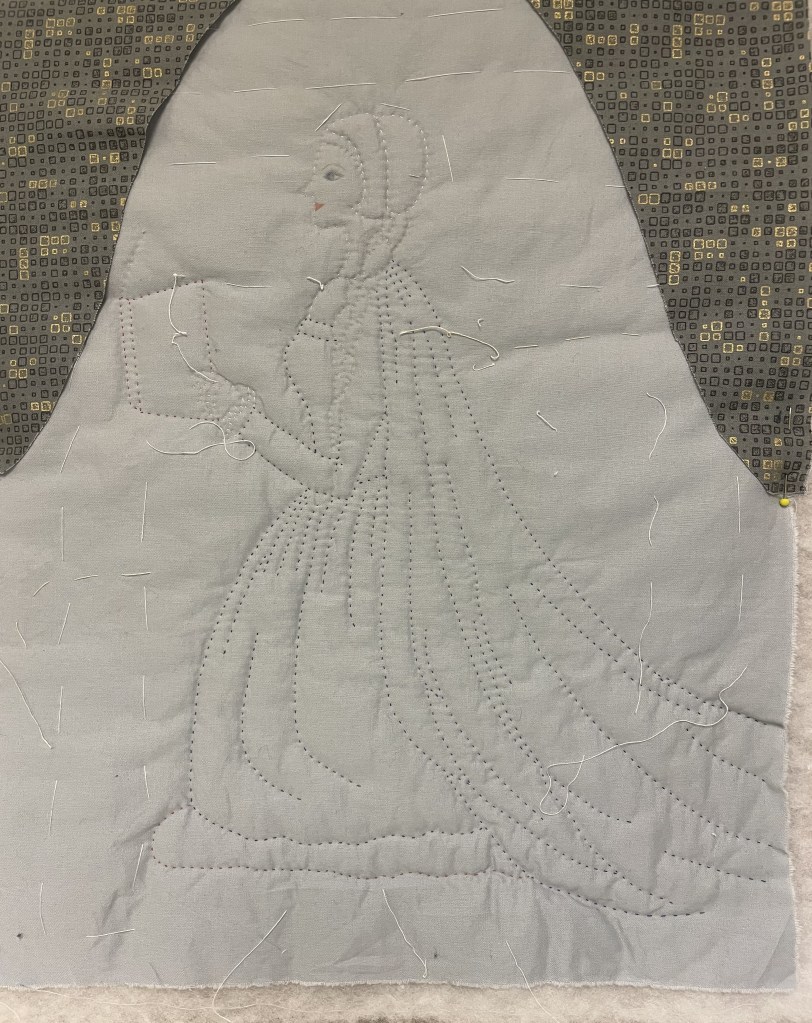

People ask me “Why Cromwell?” They look at my stitching and ask “Why Cromwell?” But I’m not stitching Thomas Cromwell, not really. I’m stitching Hilary Mantel.

“Little Miss Neverwell”

I first came across Hilary Mantel and her writing as a much younger woman. Back in 2003, I had lived with endometriosis for about 20 years, although for the first decade I didn’t have a name for it. All I knew was that I used to faint with pain every month – in classrooms in Stalybridge, and later in offices in London. It used to be called “period pain”, and I was ashamed. I would be told I was making a fuss; that it was my fault for not having had breakfast; that I should take more exercise; that I was too fat; that for goodness’ sake what was the matter with me, always ailing?

But in 2003, I heard a voice on the radio reading a book called Giving Up the Ghost by Hilary Mantel. I was at home recovering from (failed) surgery aimed at treating my endometriosis. I think I had quite a lot of nerve endings in my abdomen excised with a laser on that occasion but it’s difficult to remember now; I had eight lots of surgery over a decade or so, and the detail has blurred. There was little public awareness of endometriosis in 2003, but the book on the radio was talking about it. In some detail. And it was making my life make sense.

I loved Hilary Mantel from that moment on. There’s a place in my heart for Giving up the Ghost, which articulated endometriosis in a way I never could. When I met her, I thanked her for it. I will never forget that she put her hand on mine and said “It is survivable”. Those were words I had waited to hear all my life. I have a photograph of that moment, and because of the way my camera works, it captured a few frames, which move. I can watch her take my hand, as a ghost of my memory.

In late June 2024, I was in Devon for the Wolf Hall Weekend, which was a celebration of Hilary’s work. I haven’t really processed the event in my mind yet, other than to note it as a magical time. But I also remember crying surreptitiously when her editor and agent mentioned the terrible impact of endometriosis on Hilary’s life. I was sitting at the front of a packed room, and, as I was compèring much of the event, I didn’t want to cry in front of everyone. Tracey – lovely Tracey – sitting a couple of rows back – saw and was so kind.

“My body is getting the better of me, though people seem to feel I am responsible for what it does.”

These were tears for Hilary, but also for me; I block out the impact that endometriosis has had on my life as much as I can, and I don’t let myself think about it. But when I got back from Devon, I reread Giving Up the Ghost. I think of Hilary’s memoir as a book about endometriosis, but in fact the descriptions of the condition don’t appear until almost the end and take up only a few pages. But they are powerfully and unshrinkingly written.

Her words gave me permission to think about the time unusable because of pain; the wasted years stagnating far too long at one workplace that made no issue of my sickness (for which I was not sufficiently grateful); managers elsewhere who thought they were entitled to make an issue of it – why couldn’t I be more “resilient”?; appointments cancelled; hospital stays; endless medication and its side effects; my shame about my body; and my wonderful partner who doesn’t complain about the impact it has on him too.

I’m not writing this for sympathy; most of the time I just get on with things and make the most of the time I can use. My dentist thinks I have a very distorted relationship with pain because I am so used to it.

And, with regard to one of the most severe impacts of endometriosis, I have been really lucky. I never wanted children. Infertility has never caused me grief. Childhood stuff, family stuff, showed me that motherhood wasn’t for me. I am happy with that.

But the emphasis placed on fertility did have an impact on my treatment. As a young woman, I learned that I was wrong to not want children. “You’ll change your mind,” was a phrase I heard over and over. And as my endometriosis progressed, I did my best not to make the “When are you going to have children?” interrogators – so rude! – feel bad. I didn’t want them to feel uncomfortable if I said I couldn’t carry a pregnancy, and I wanted to be truthful, so I said I didn’t want to. And we’d be off. “What never? Oh girls say that but they don’t mean it. You’ll change your mind.” I would seethe inwardly wanting to shout that they weren’t listening and why didn’t they go and torment someone else. Only once, when confronted with a particularly persistent stranger I eventually cracked. “I won’t be having children. I have severe endometriosis and I am having a hysterectomy in about three weeks’ time.” Undaunted, this woman who didn’t know me at all promised she would pray for me. A miracle baby would be mine. A miracle for whom? I muttered.

Sadly, that mindset was also rampant in the medical profession. How many times did I hear that having a baby would deal with the endometriosis? I would sit there thinking that it was a poor reason to get pregnant. Or that this or that doctor had once had a patient who had changed their mind so no, they wouldn’t offer a hysterectomy because I too would change my mind. I was being a Bad Patient. It was exhausting. The same conversation every single appointment for years and years. My GP was sympathetic but she couldn’t get through the gatekeepers up the line.

But eventually, after passing out on the bathroom floor at home, and being nudged back into consciousness by a curious kitten, there was tentative agreement that more radical surgery might be possible. If I am Good.

“Some inflamed growth inside me was bending me down at the waist, pulling my abdomen, knotted with pain, down towards my knees.”

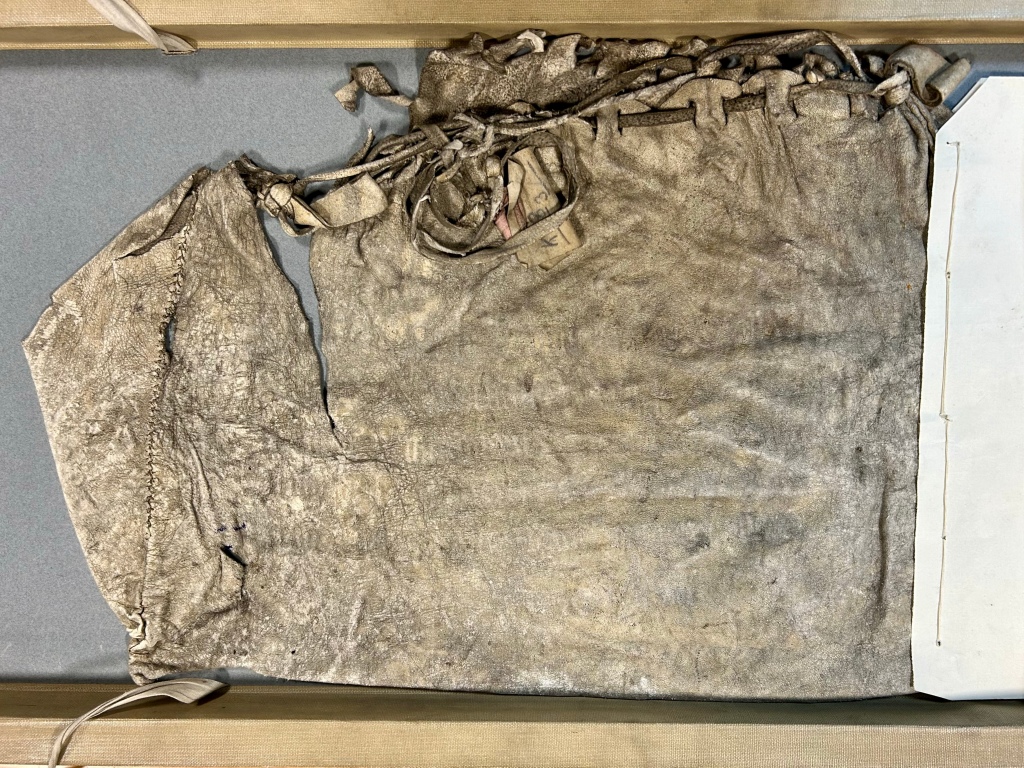

“Oh! That’s you!” said the surgeon, opening my file. “My students get to see you all the time. I use you in teaching.” I look down at the file on his desk and see a brightly coloured photograph. I expect to see my face, but it’s something different and it takes me a little while to realise – that’s my womb. There are blackish spots and lesions all over it. That’s my endometriosis. I am a teaching aid. I wish I didn’t know that. He tells me that now I am 35, he thinks I am “old enough” to know my own mind so he will grant my wish of a hysterectomy. But there’s one condition. My partner must accompany me to my next appointment, so that the surgeon can assess our relationship, how serious it is, and whether I am depriving A Man of his Right to Fatherhood.

My partner is not amused. Taking an afternoon off work to go and talk to a surgeon who lacks the ability to believe a woman – whose own word is not to be trusted – who has been telling him for seven years that she doesn’t want children. It goes against his values, my values, and our joint values. But it must be done. We go to the hospital and see Mr Surgeon. Mr Surgeon tries to open a dialogue about how my partner feels about this. My partner will not play ball. “It’s her body. Not mine,” he says and I cheer inwardly. My partner is wonderful. We leave the hospital and sneak off to see Master and Commander on the big screen in the middle of the afternoon. Master and Commander continues to be one of my favourite films.

So on Wednesday 7 April 2004 I finally have my hysterectomy. I am scolded by Mr Surgeon before the operation for insisting on being cut open. I have deprived his students an opportunity to observe keyhole surgery because I am Difficult. I am a Bad Patient. Inwardly I think of Mr Surgeon’s photograph and decide that Mr Surgeon’s students have observed enough of me, thank you very much. But the anaesthetist is nice, and talks to me about John Noakes and Blue Peter while I count down from 10.

When I wake up, my womb is gone, and, while they were in there, they took my cervix too. I wasn’t expecting that but never mind. I believe that’s it. My stitches are removed, and the long scar starts to fade. My endometriosis is over. But.

“Now my body was not my own. It was a thing done to.”

I am back in the surgeon’s office, for a post-surgery catch up. All satisfactory, the surgical team are pleased. I am a Good Patient again, despite my temerity in exercising choice over the type of surgery. I report that I am recovering well and feeling a lot better. Mr Surgeon looks at his notes and mentions – casually – that he had to leave some endometriosis behind and that it might continue to trouble me. There were strings of it in a tricky place, apparently. In fact there still are.

“It was too risky to remove it.”

“Oh”, I say, suppressing my anger, not asking “If you had agreed to operate seven years ago when I first asked you, would it be there at all?” Instead, I say thank you sweetly, politely, smiling, smiling, smiling, so grateful. Inside I am burning with rage.

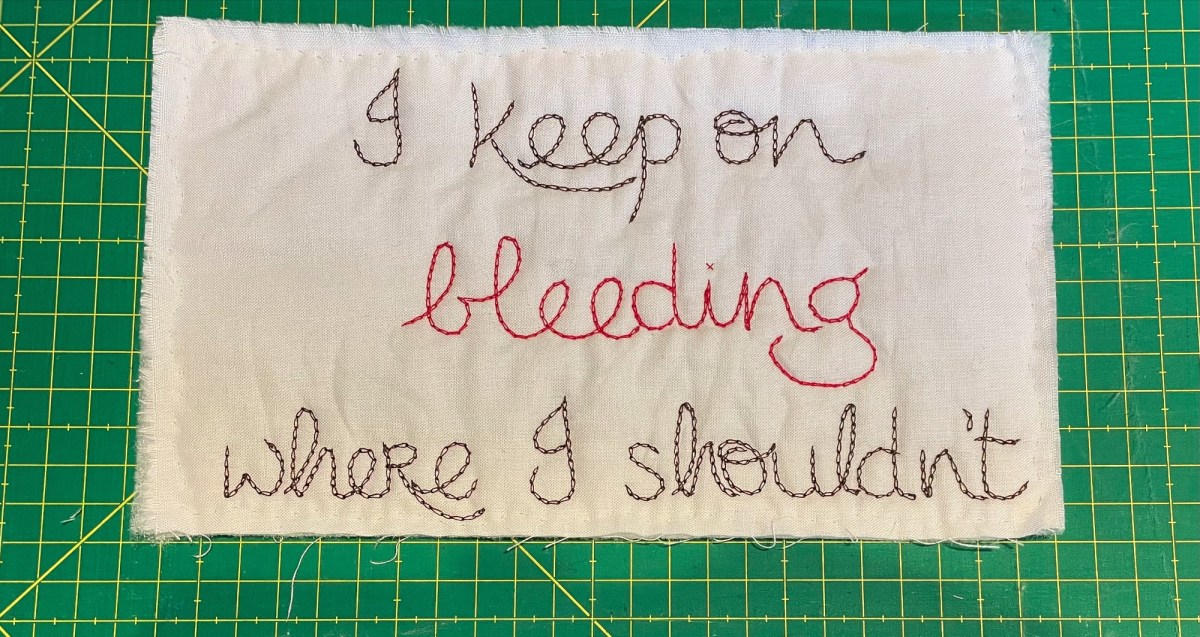

The rage turns into regular monthly migraine. Or perhaps it’s not rage but yet more hormonal shock. I might not bleed any more, but the endometriosis finds another way to make itself felt. Dull aches, flare ups. Being bent double from time to time. The new world of monthly migraine wastes my time, makes me incoherent, puts paid to full-time work. Despite all that surgery, my body will still not behave. But at last I am a Good Patient, and I don’t make a fuss this time. I just put up with it.

The last word should go to Hilary. From Giving up the Ghost:

Just which bits of you are left intact? I have been so mauled by medical procedures, so sabotaged and made over, so thin and so fat, that sometimes I feel that each morning it is necessary to write myself into being… When you have committed enough words to paper you feel you have a spine stiff enough to stand up in the wind.

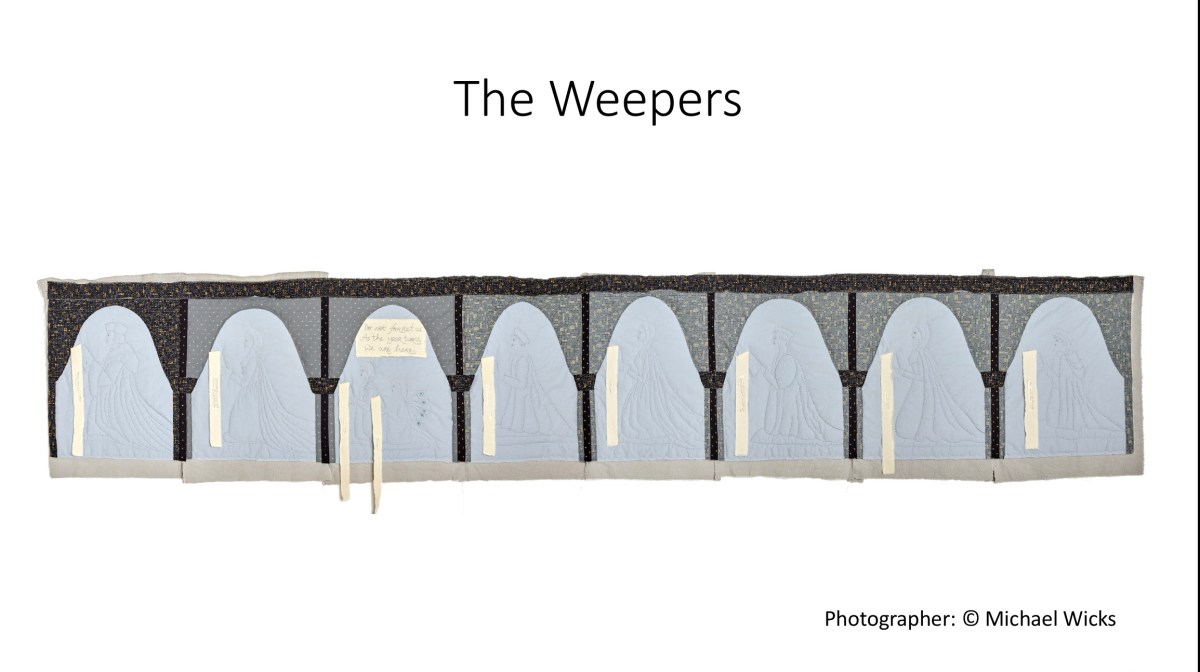

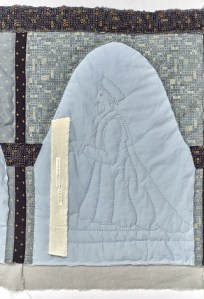

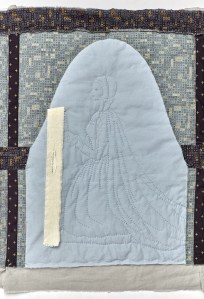

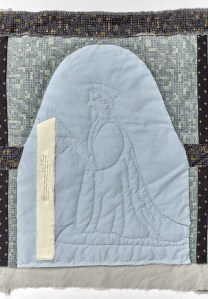

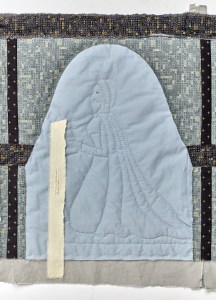

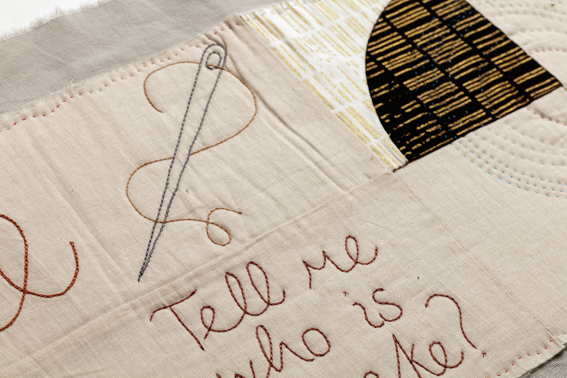

She says what I cannot. I do this too. Except in my case I stitch myself into being. And I stitch myself into being through the medium of her Cromwell. But really, it is all about Hilary Mantel herself.