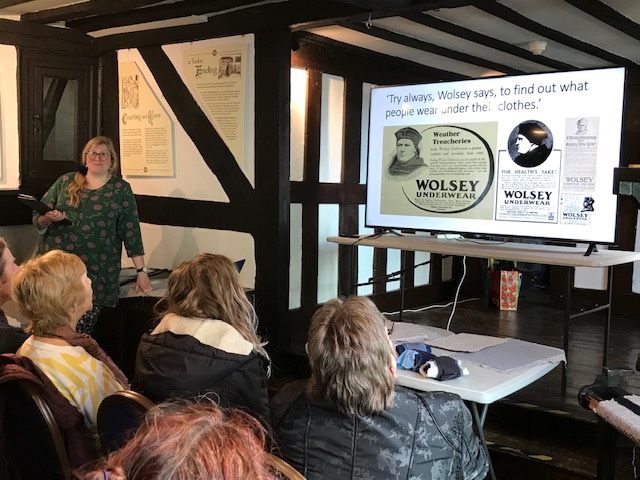

I recently spent a very enjoyable few days out of London, having been invited by Hilary Mantel scholar Dr Lucy Arnold and the Tudor House Museum in Worcester to take part in a public event at the Museum entitled “In the Weave”. We are both fascinated by the role that textiles play in Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy, and we were delighted to share our enthusiasm with an engaged audience, many of whom left planning to read or re-read Wolf Hall. Lucy talked about the role of textiles and the textile trade in the Cromwell Trilogy, and how these appear in the text, while I shared my analysis of who stitches and what they stitch across the Trilogy, and talked about some my textile work.

I have written before about the complex relationship I have with the first Wolf Hall quilt, the circumstances in which it was made, and how I feel it doesn’t really work as a piece. However, taking it out for the first time in nearly a year, laying it out, folded loosely, and watching people handle it and photograph it made me start to question my relationship with it. Does it in fact work? And does it have potential for further development?

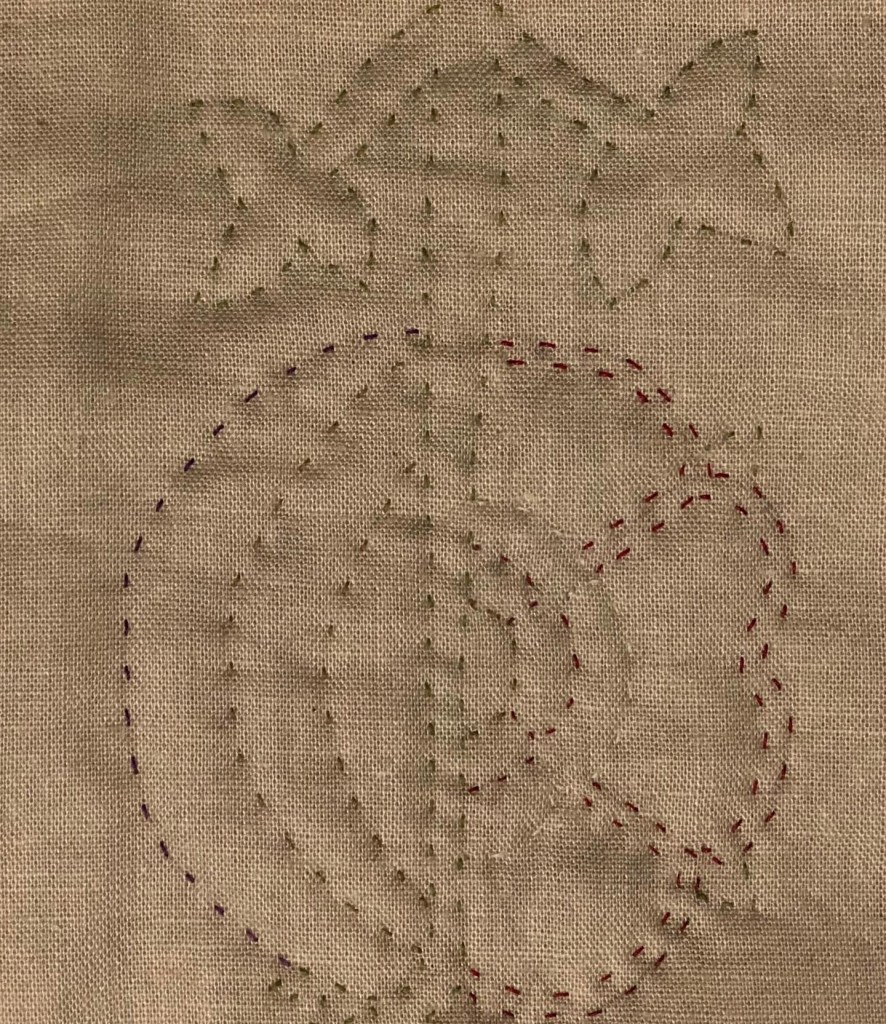

This time last year, I put aside the stitched chapter titles I made back in 2020 for Bring Up the Bodies and The Mirror and the Light. I didn’t want to use them then. But I’m now wondering if that 46 feet of Wolf Hall quilt might like to grow further? I had completely forgotten that I left the end unfinished, open to further work should I choose to add to it.

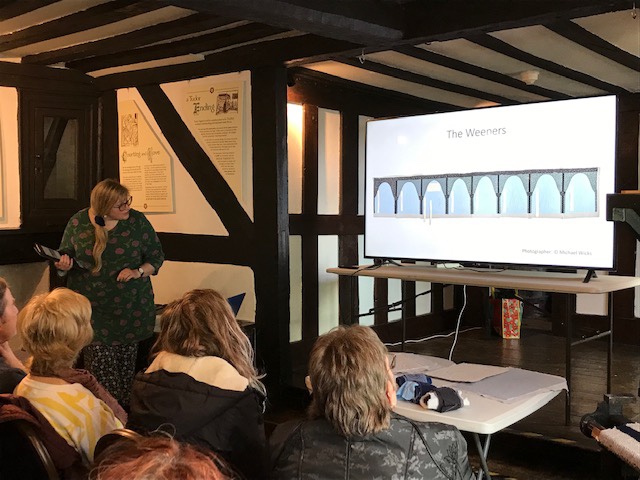

While in Worcester I took the opportunity to visit the Cathedral. There was something particular I wanted to see – the tomb of Prince Arthur and his Chantry Chapel. I was very fortunate to visit at a quiet time, so I had the Chantry to myself and thus an ideal opportunity to look closely at carvings and symbols. The Chantry was vandalised during the reign of Edward VI, and some visible scars from axes and swords can still be seen, scars I found unexpectedly upsetting.

I had assumed that the Chantry was Prince Arthur’s burial place and that it a mourning Henry VII and Elizabeth of York had been involved in its design and construction, but according to this wonderful piece by Lucy Arnold, it seems that we don’t actually know exactly how the Chantry was built, where Prince Arthur was/is buried, or how much the memorial cost. Interpreting material items left to us from centuries ago is often challenging, partial, and ambiguous.

I was interested to see pomegranate symbols both inside and outside the Chantry – the symbol of Katherine of Aragon, Prince Arthur’s widow. These symbols are survivors of destruction – both during the reign of Henry VIII and Edward VI:

They search out and obliterate any trace of Katherine, the queen that was, smashing with hammers the pomegranates of Aragon, their splitting segments and their squashed and flying seeds.

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies – Falcons

But far more unexpected than the surviving pomegranates, was Master Secretary Cromwell himself. Walking in the Cloisters, I looked in detail at the stained glass and, to my surprise, there was Thomas Cromwell, his hand over his mouth. What is he doing?

Perhaps Henry can tell us:

He is better than you at keeping his face straight. I see you, when we sit in council, with your hand before your mouth. Sometimes, you know, I want to laugh myself.

Henry VIII to Thomas Cromwell: Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall – Anna Regina