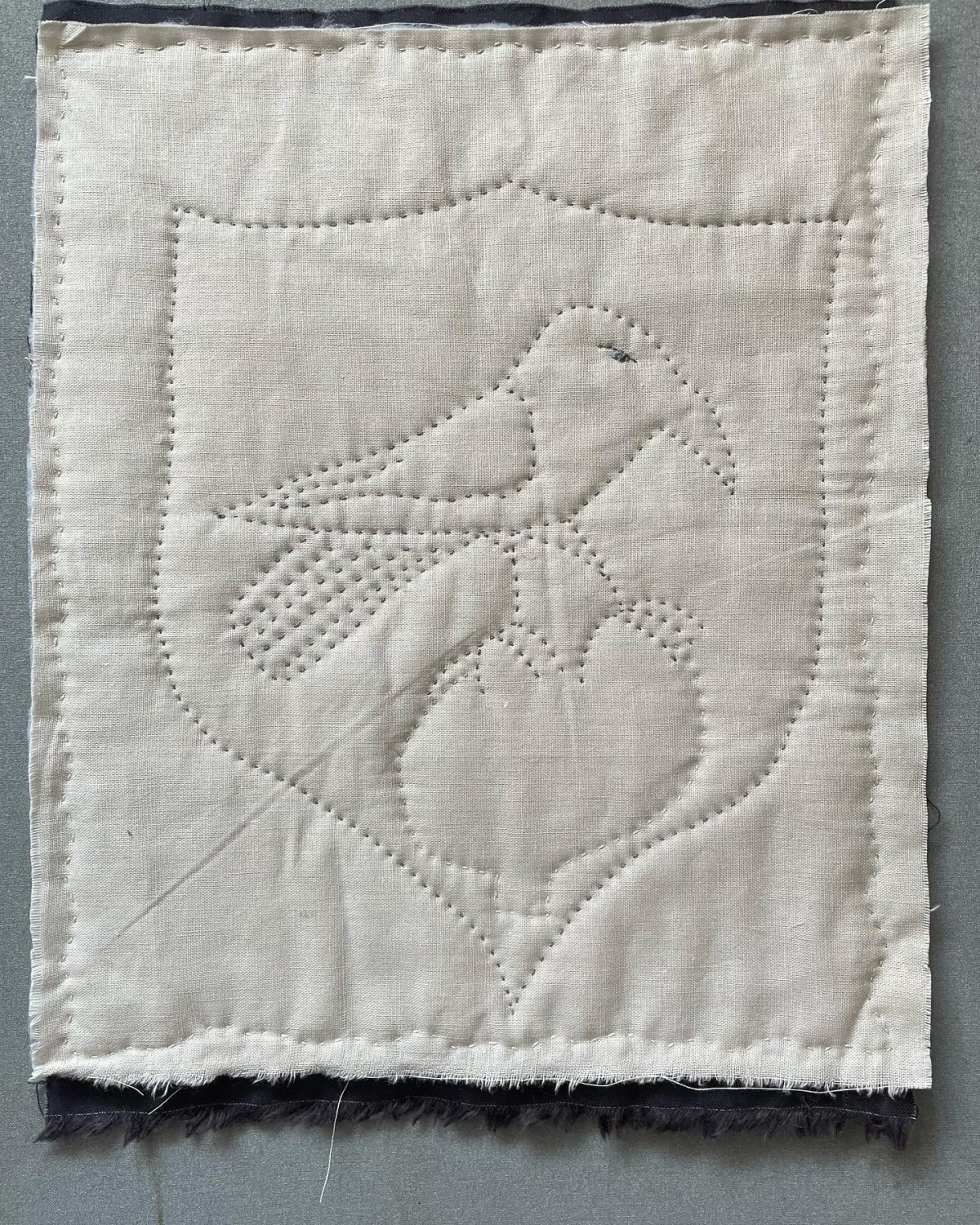

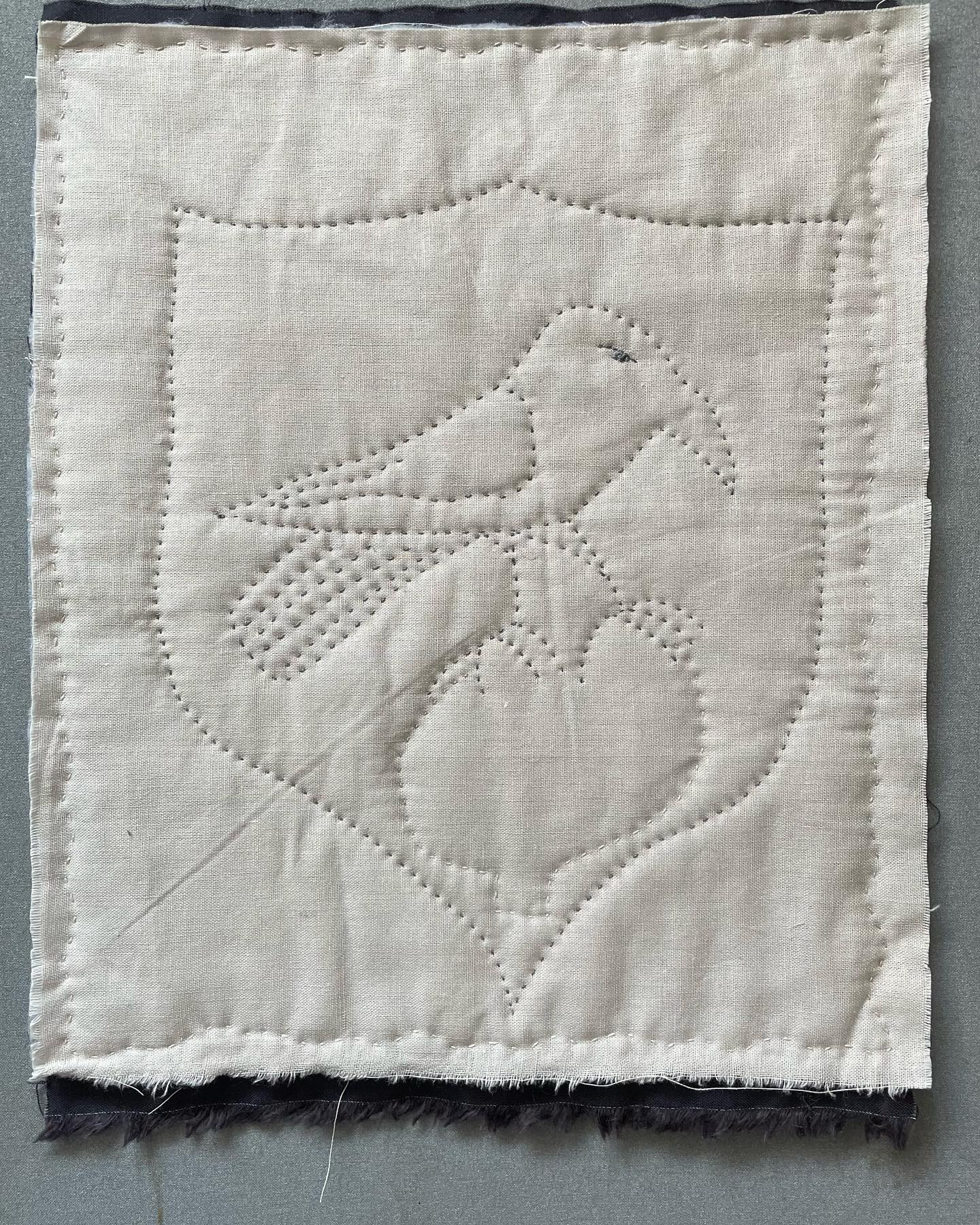

Twenty five months ago today – on 19 August 2021 – I put the last stitch into the First Wolf Hall Quilt. I’d spent a very uncomfortable few hours joining all the sections together to make forty six feet of quilting, and had struggled while wrestling the writing and coiling length into one long roll.

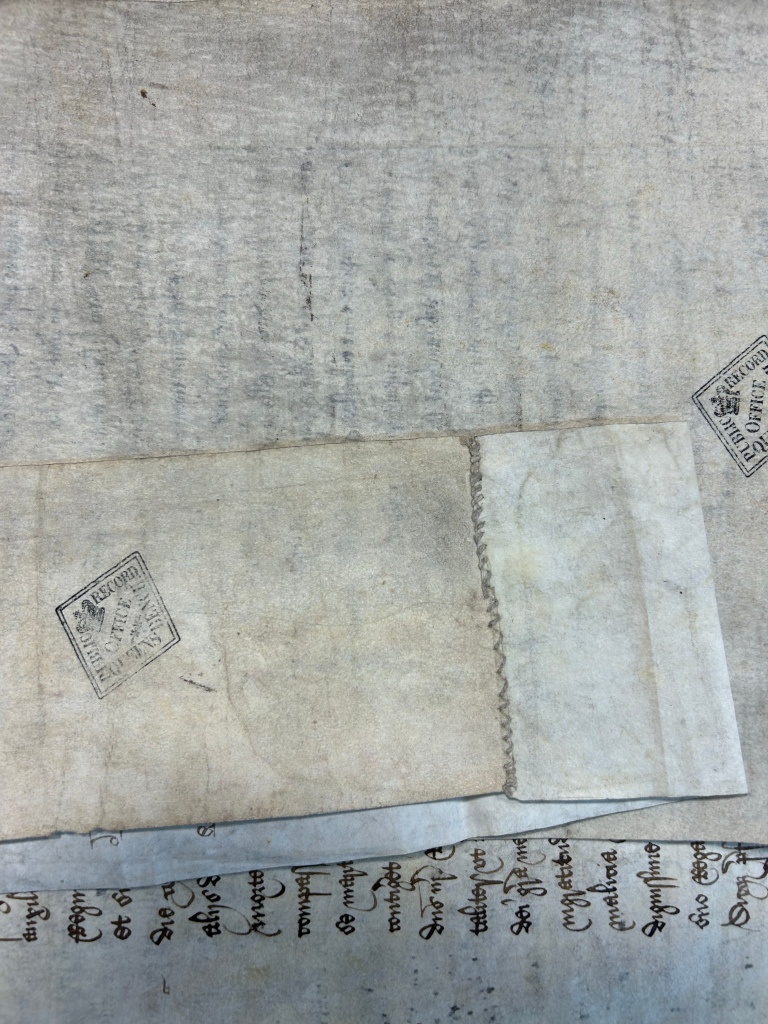

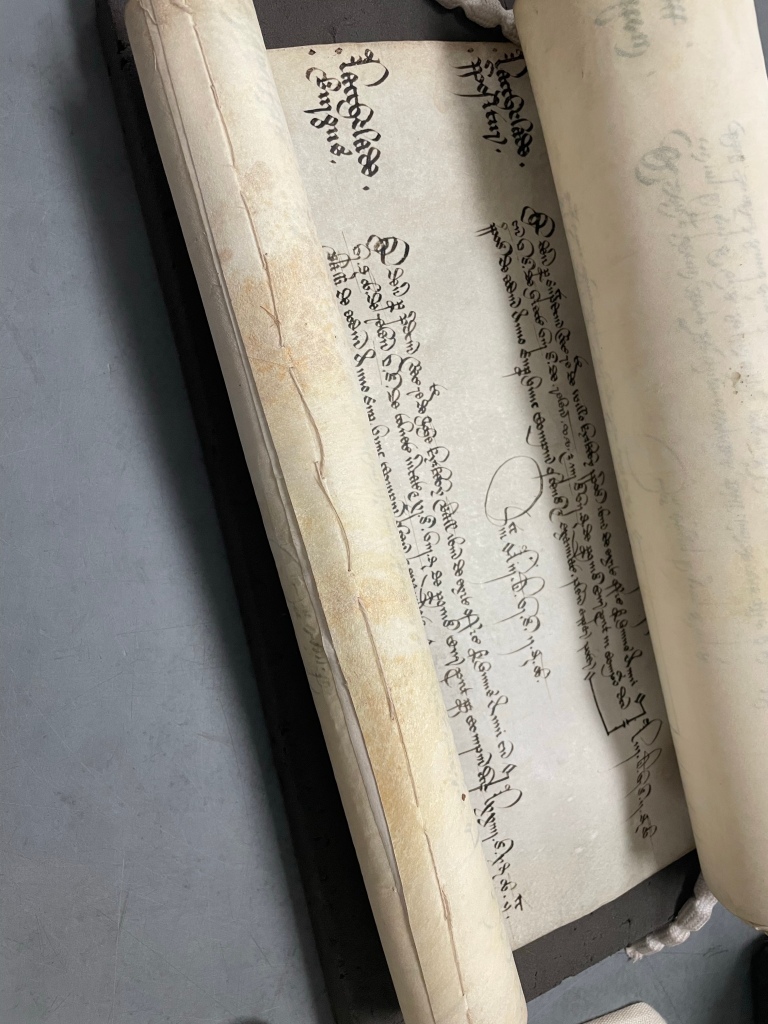

More recently, I have been regularly visiting the National Archives at Kew, just outside London, looking at Sixteenth Century documents relating to Thomas Cromwell. Such documents – especially those that take the form of rolls – are often stitched together. This gives me a feeling of continuity – these old parchments and my quilting are hand-sewn together with needle and thread, joining narratives and the historical record.

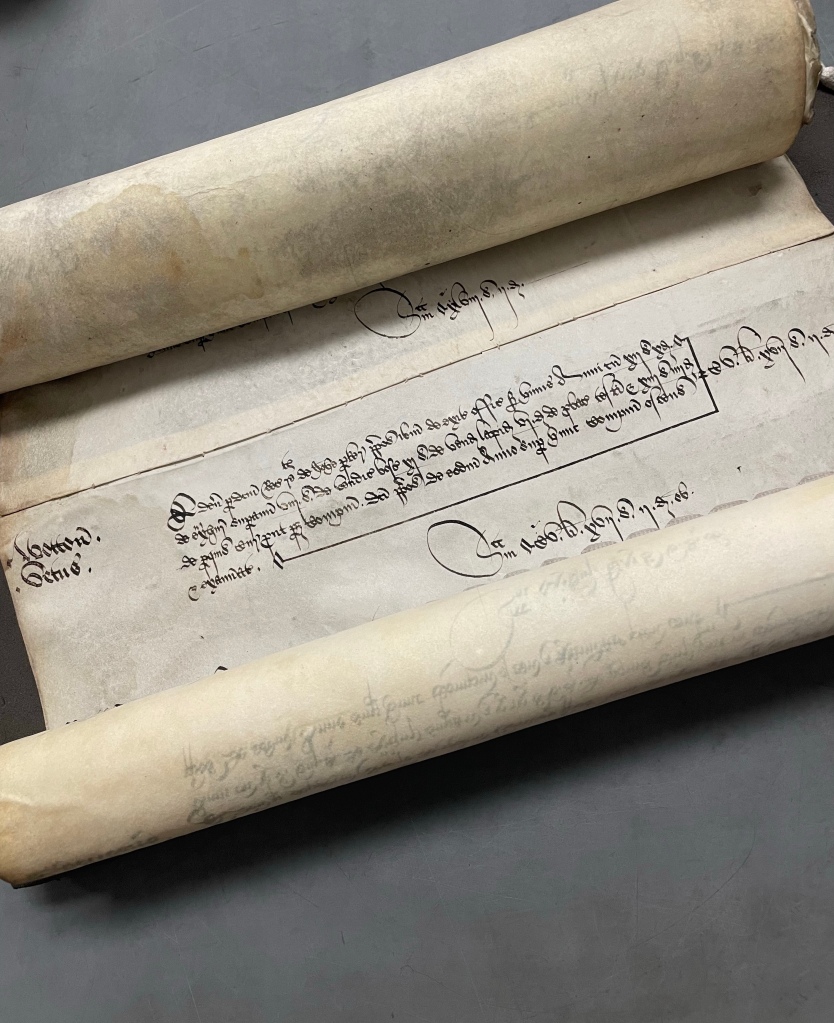

Many documents are stitched together at the top – or the end that eventually forms the core of the roll. And, having been rolled up for centuries, contents can be challenging to untangle. On numerous occasions, I haven’t dared unroll very far for fear of damage. Sometimes, I can’t find the end and struggle to unroll in such a way to avoid different membranes springing back.

Despite the frustrations of working with these rolls, I love them. I love seeing the stitches, and I love the act of unrolling bit by bit, an inch at a time, and not being able to see the whole document at once. It reminds me of my rolled quilted interpretation of Wolf Hall, which cannot and should not be seen all at once.

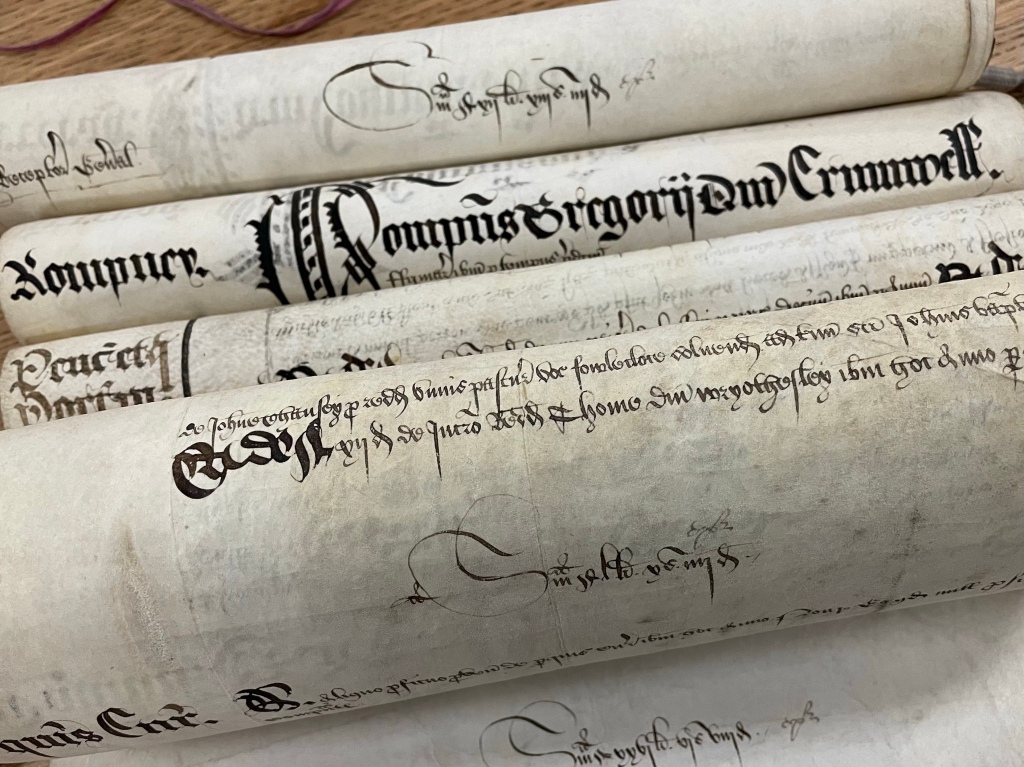

Some invaluable surviving documents are not rolled, but preserved flat, boxed carefully under lock and key. These are King’s Bench documents from 1536 – and they are from the trial of Queen Anne Boleyn and the men accused of treason alongside her.

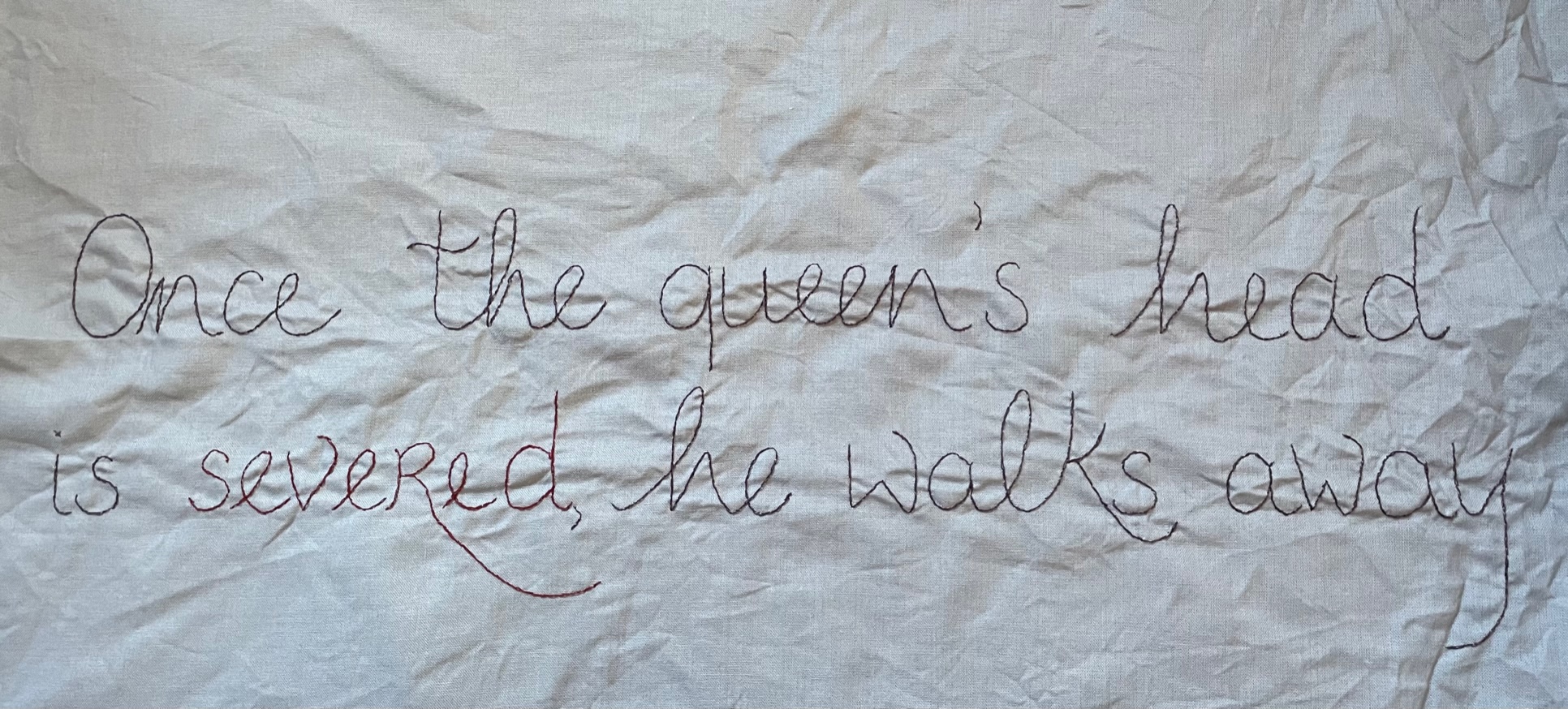

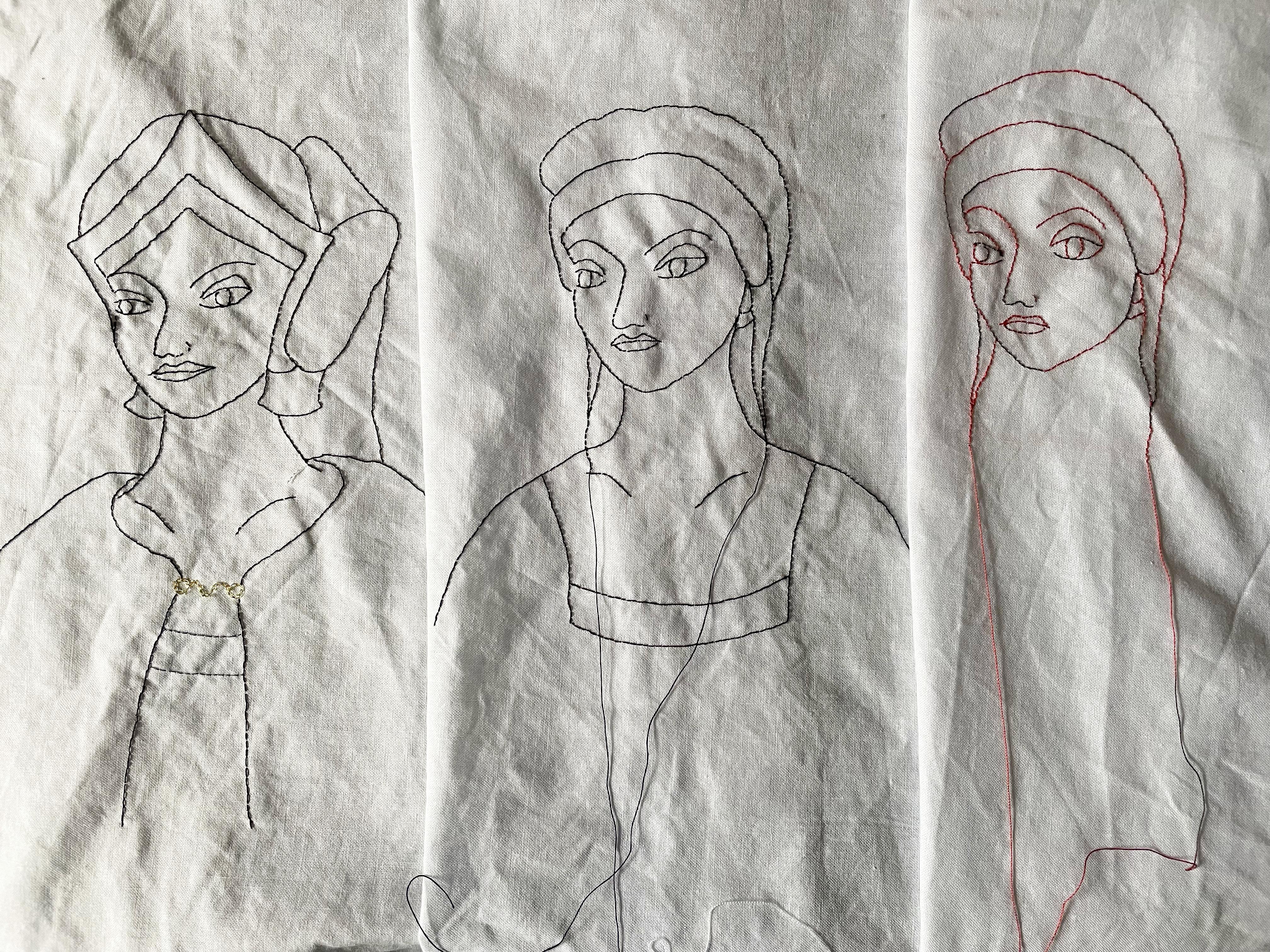

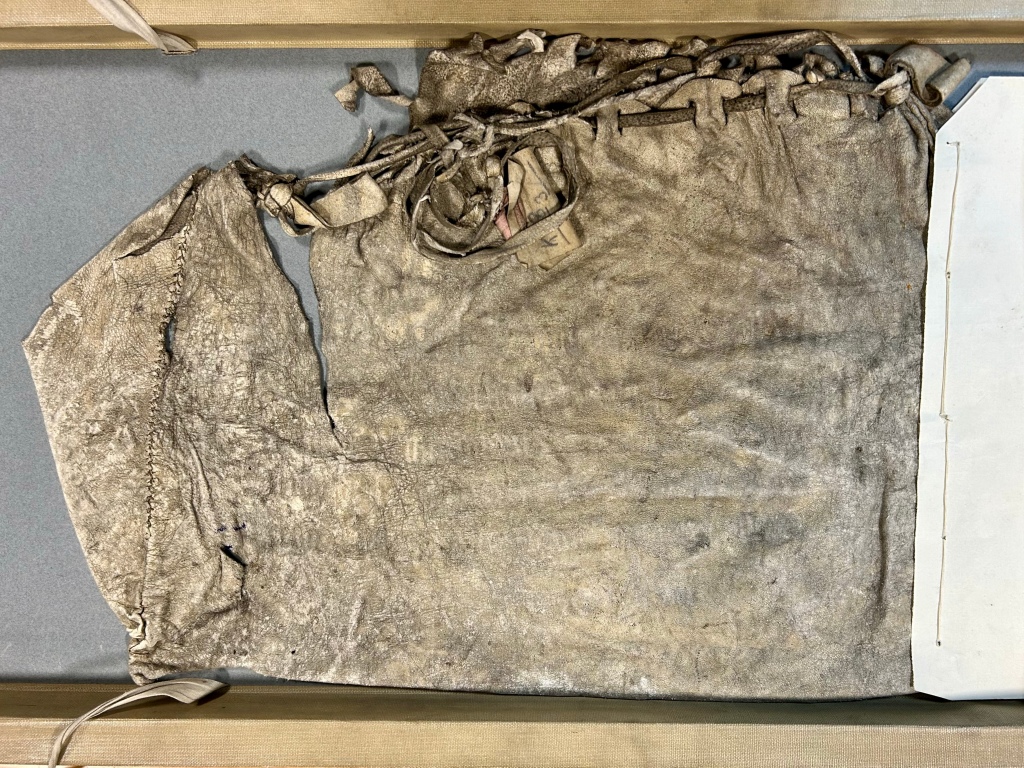

Today, I saw documents listing the names of George Boleyn, William Brereton, Francis Weston, Henry Norris, and Mark Smeaton – the men accused with the queen. Their names are clearly readable in beautiful script – but there’s something very unsettling about carefully controlled handwriting when it documents death sentences. I have never had such a strong visceral reaction when looking at documents before. These papers carry a weight of pain, grief, fear, death, and betrayal. I felt shaken just brushing my hand against them, and against the remains of the leather bags in which the documents were once carried.

These papers remind me of the stage play of Bring up the Bodies. Gregory asks his father whether the executed men are guilty. And he clarifies, “I didn’t mean, ‘Did the court find them guilty?’ Father. I meant, ‘Did they do it?’” Thomas replies: “Who knows?”

The trial papers include documents that were extended by the careful use of herringbone stitch. As Hilary Mantel wrote in The Mirror and the Light, “it’s useful to have the evidence stitched together”. But even today, this stitched together evidence is controversial, contested, unreliable, shifting. The stitches don’t strengthen the evidence, but they strengthen its documentation.